Show Your Work: How to Justify Your Decisions & Get Stakeholder Buy-In

Last month, I spoke at Mind the Product San Francisco. The following transcript is how the speech was written and does not match the talk exactly.

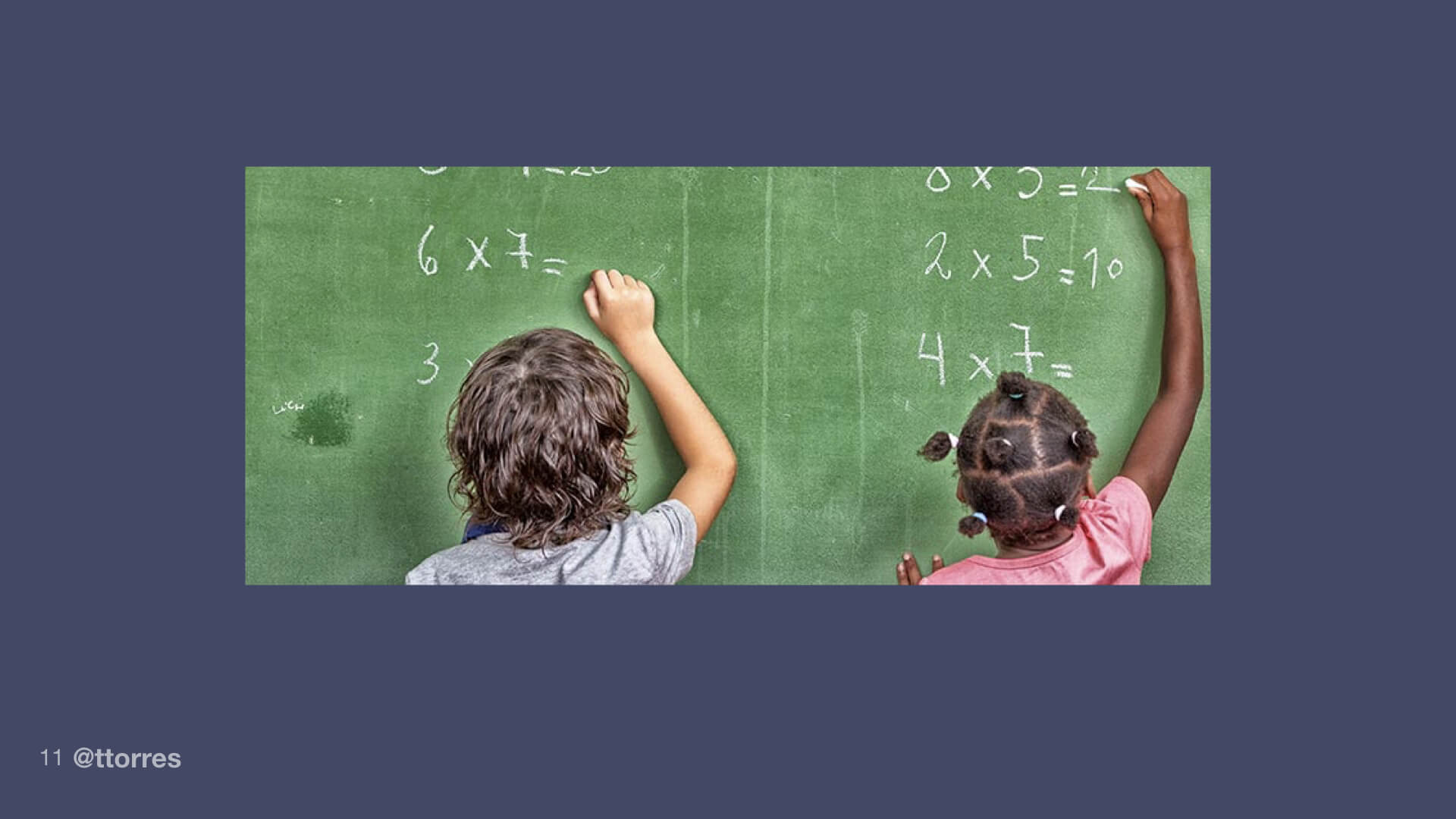

I want you to take a minute—think back to elementary school when you were learning multiplication tables.

Don’t worry; I’m not going to make you do any math.

I was in third grade. We used to do these one-minute timed tests. It was a full sheet of multiplication problems and you were supposed to go as fast as you could. As soon as you were done, you put your pencil down and your hand up.

There was one boy who I competed with day after day. We always finished one-two. He’d win some, I’d win some. I loved the thrill of putting my hand up, hoping to be the first one.

But it wasn’t just about being fast—you couldn’t make any mistakes. You had to go fast and get it right. This motivated me to practice. I wanted to get all the right answers.

Now fast forward in time. Do you remember learning algebra?

I was in eighth grade. I was what my algebra teacher called a half-lesson learner. I was doing my homework before he was done teaching the lesson.

Algebra, also, was about getting the right answer. I loved flipping to the back of the book to confirm that I got it right.

But there was more to algebra—you might remember. We had to meticulously work step by step until we got to the right answer. We had to show our work.

I wasn’t very good at showing my work. My brain worked faster than my pencil and I didn’t want to slow down. As soon as I confirmed that I got the right answer, I was on to the next problem.

Fast forward in time again. This time I’m in a computer science class in college. The days of always getting the right answers are long gone.

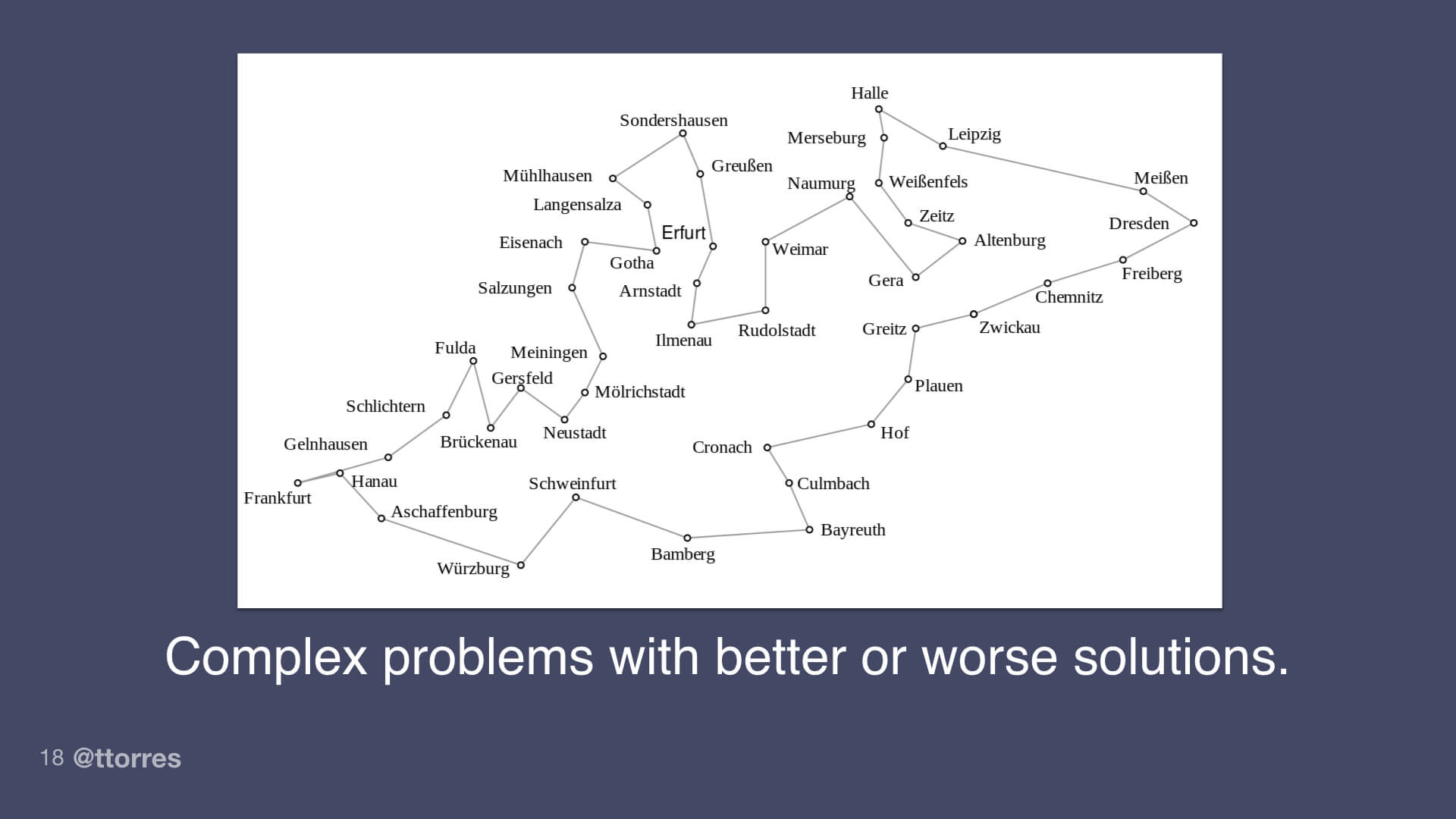

Many of the problems we worked on didn’t have right answers. They were too complex. They weren’t solvable. They were designed to test our thinking—not to lead us to a right answer.

I remember the first time I tackled one of these problems. I was devastated. I didn’t know there was no right answer. I just knew that I couldn’t find one. Hoping for partial credit, I did the best I could. It turns out, I did just fine.

I didn’t know what to make of this. I liked that I got a good grade, but I yearned for a right answer. I found comfort in right answers.

Looking back on this journey starting with rushing to find the right answers in elementary school to learning to show my work in eighth grade to letting go of the right answers in college, I realize we are on a similar journey within our own organizations.

Now to illustrate this journey, I’m going to use Netflix as an example. So let’s start with a disclaimer. I’ve never worked at Netflix. I’ve never coached teams at Netflix. I have no first-hand knowledge of what it’s like to work at Netflix. I use Netflix as an example only because I suspect most of you are familiar with their product.

I suspect that if you were tasked with improving the consumer experience on Netflix, you could easily generate a list of prioritized improvements.

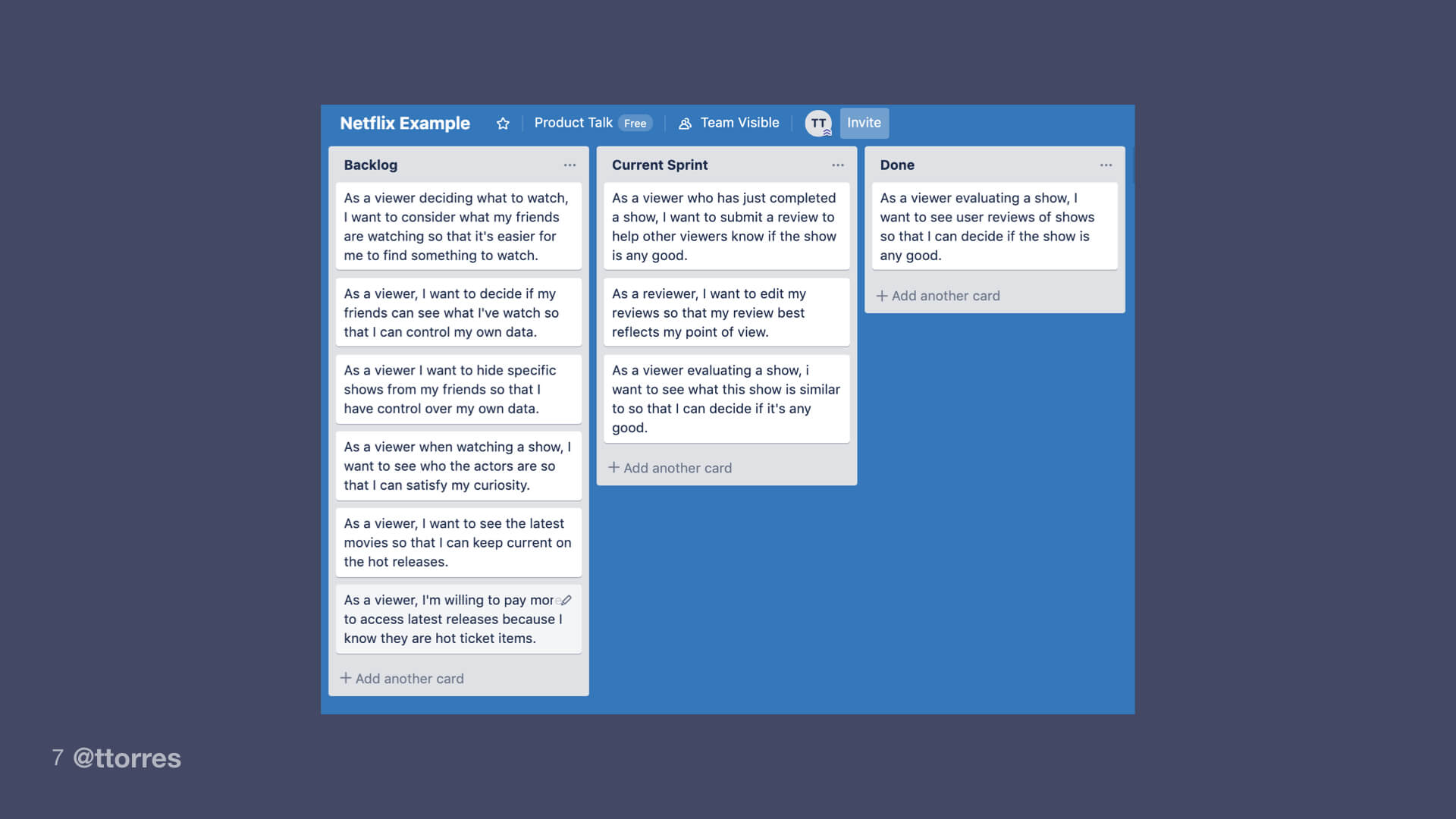

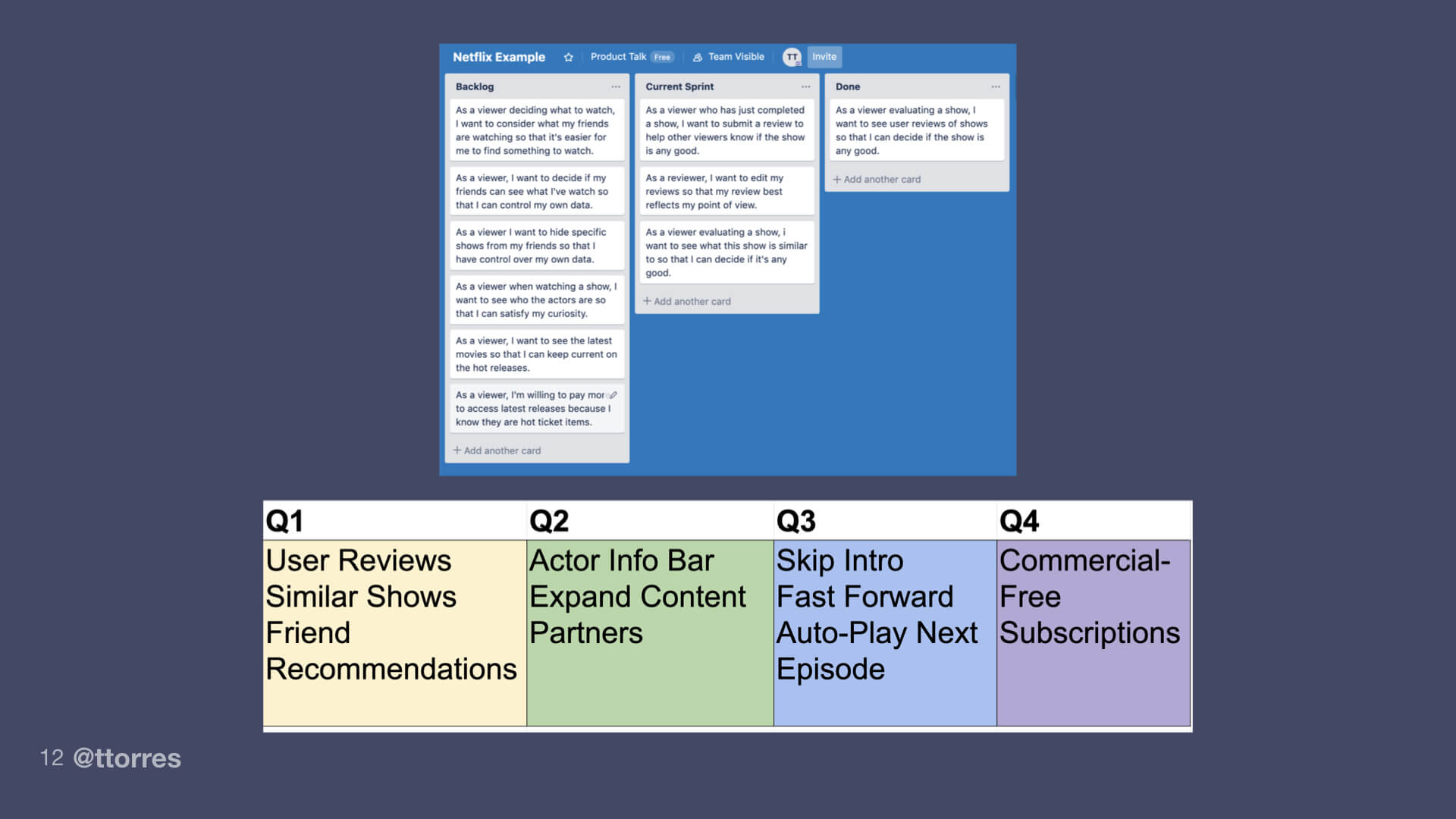

You could fill backlogs with user stories.

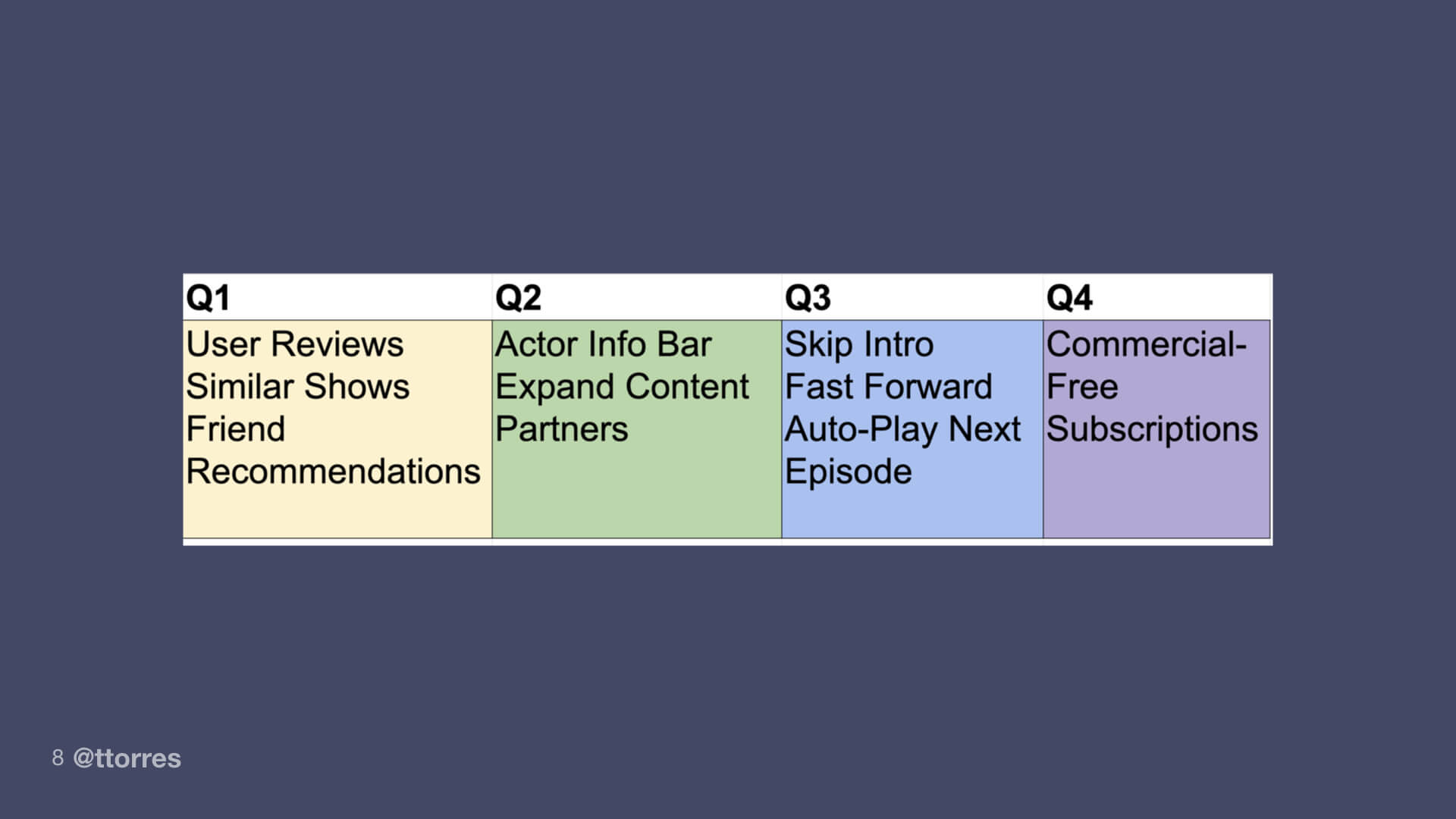

Every one of you could create a 12-month roadmap.

After all, this is what we do as product people. We create plans. We plan for the future. We find comfort in being prepared—in having the right answers.

If we are young in our product practice, we obsess about those right answers. We work to find them as quickly as possible.

In meetings with stakeholders, we advocate for our point of view. We’ve all been there. We resist any suggestion to change. And when we get pushback, we yearn for autonomy.

When our boss tells us to build something else, we complain to whoever will listen. We curse the dreaded Hippo.

We get frustrated. We know we already found the right answer. And it’s perfect. But nobody will listen.

We start dreaming about our next promotion. Thinking that when we are the Hippo maybe our perfect answers will finally see the light of day.

We are like the third graders rushing to the right answers as quickly as possible.

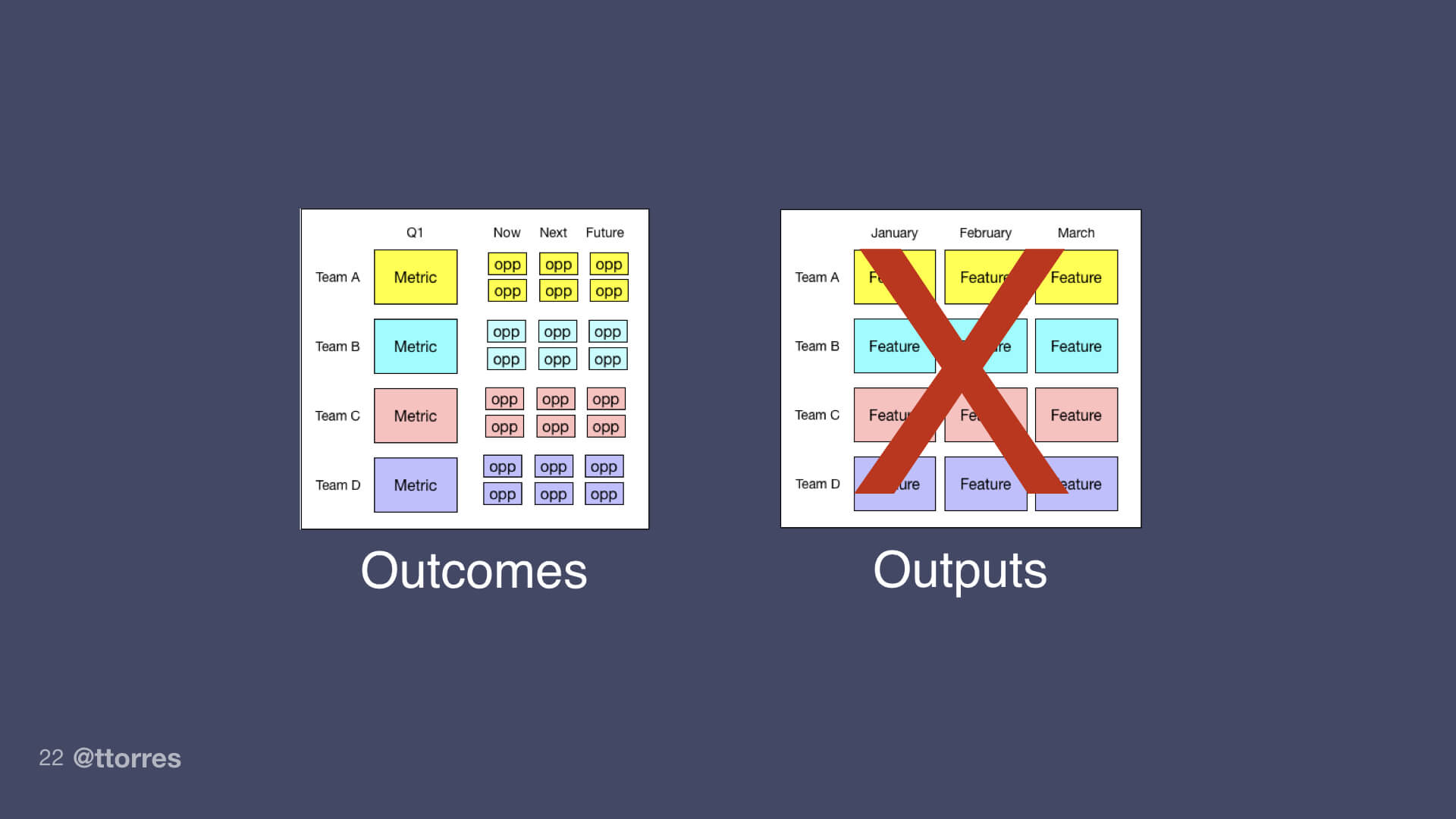

What we don’t realize is that we are creating this stakeholder problem ourselves. When we only present the right answers—the backlogs full of user stories and roadmaps full of features and release dates—we are asking our stakeholders to give us their opinions on those outputs.

And more often than not, they are going to have their own opinions about what you should build. They aren’t going to be aligned with your opinions because you haven’t shown your work. You haven’t shown why these outputs matter.

And we all know when a Hippo has a different opinion, the Hippo always wins.

As our product practice matures, we learn it’s not just about the right answer. Like the algebra student, we learn to show our work. We learn to defend our decisions.

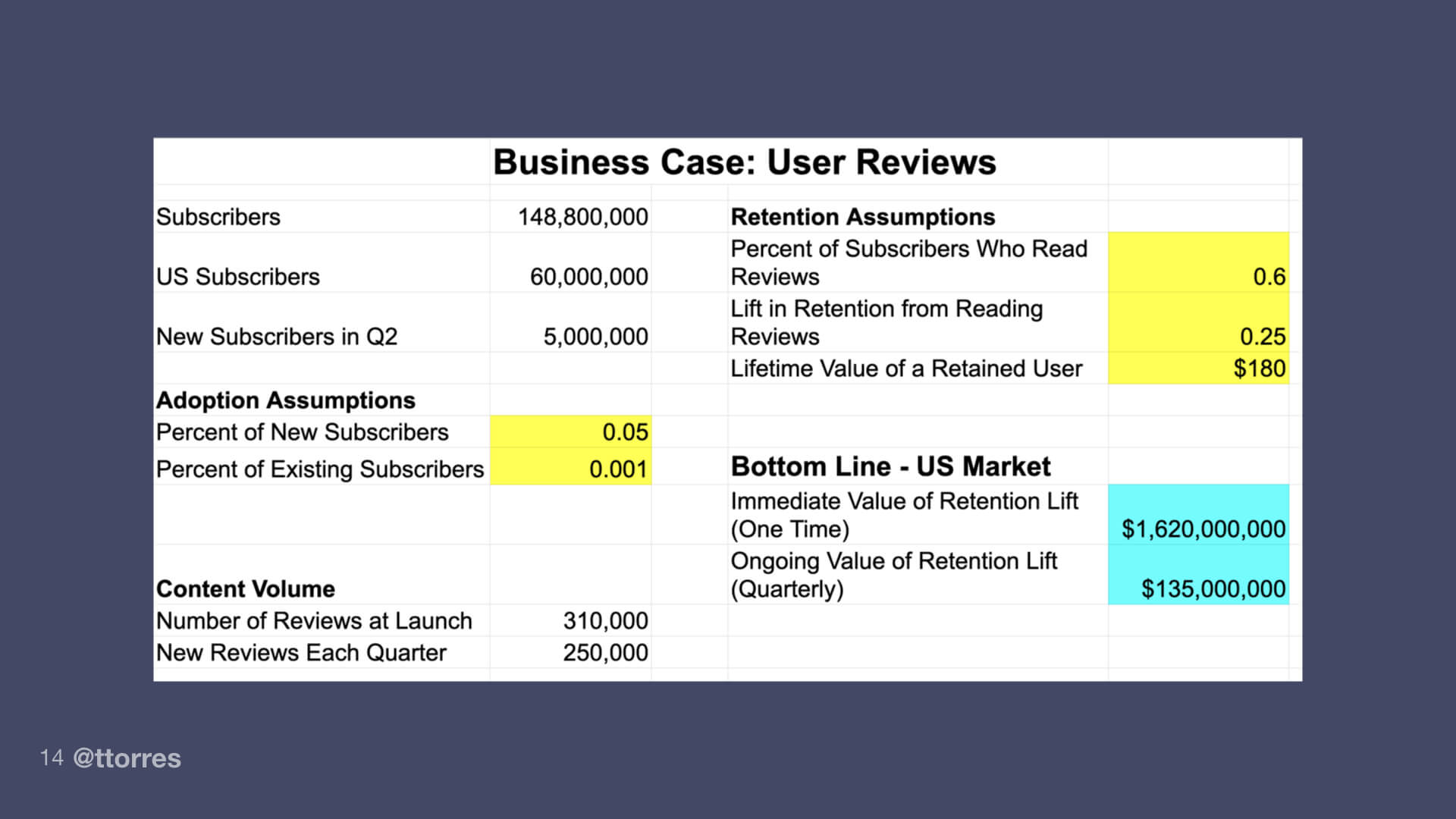

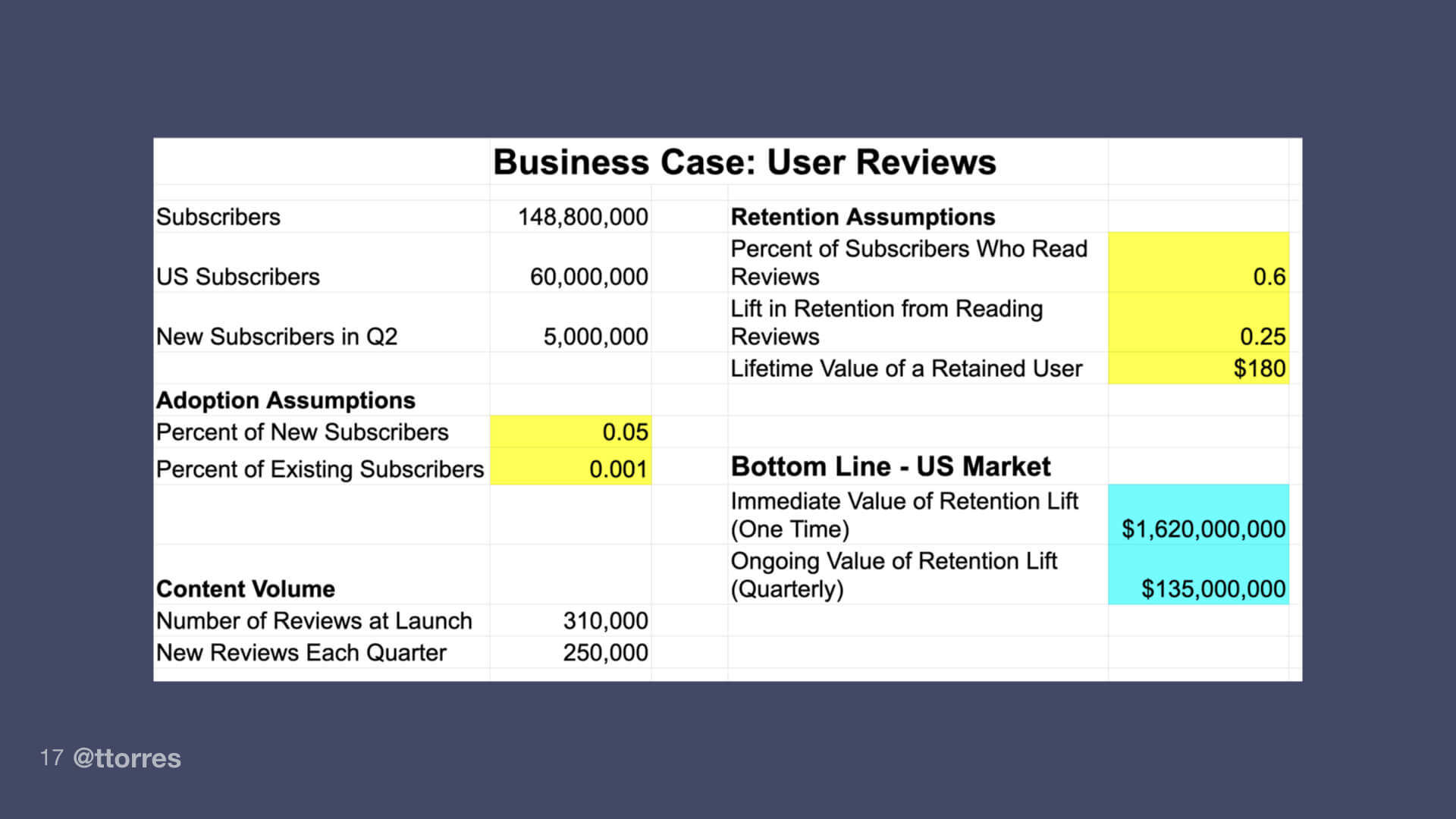

We bolster our argument for the right answer with data. We talk about total addressable markets and returns on investment. We learn to write business cases. We learn to speak the Hippos’ language.

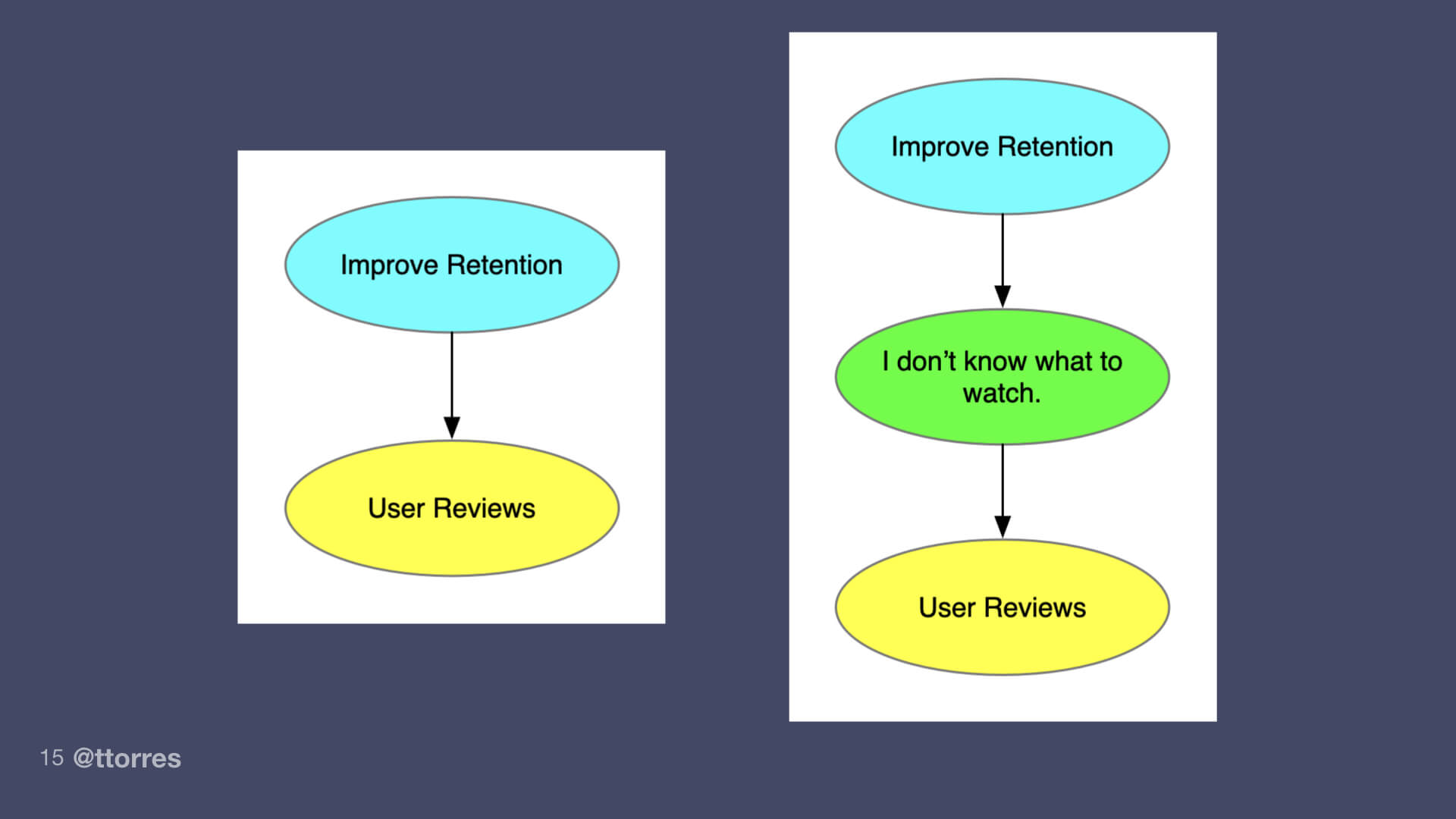

We draw a straight line from the business need to our solution. The more sophisticated among us may even draw a line from a business need to a customer need to our perfect solution.

It’s beautiful. Just like an algebra problem. We can’t flip to the back of the book fast enough to confirm that we got the right answer.

We’ve given our stakeholders more to react to. It’s no longer just about the right answer. They can give us feedback on our numbers. They can question our data. They can help bolster our arguments or point out flaws in our logic.

They can ask, “Why do you think 5% of new subscribers will create reviews?” If you’ve done your discovery work, you can present evidence that supports this adoption rate.

Your stakeholders can adjust your numbers. Maybe your boss just learned that lifetime value went up to $220 this quarter. Great, that means your idea is even better than you thought it was.

On the other hand, a general manager might highlight that no single feature has ever had more than a 2% lift on retention, suggesting that your 25% lift estimate is way too high. You might need to revise your numbers down.

Now the conversation isn’t just about the final answer. You are leveraging your stakeholders’ expertise. You are letting them question your thinking.

As a result, you get better engagement from your stakeholders and your idea gets better.

But we still have a problem. If our stakeholders disagree with our final answer, we still haven’t given them any alternatives. We still fall into the trap of debating our right answer vs. their right answer.

Our stakeholders can always create an equally good or better business case for their own ideas. This is what stakeholders do. There’s no way for us to prove that our idea is the one best idea because there is no one best idea.

And if they like their idea better than ours, they will find fault with our work.

Once again, the Hippo always wins.

As our practice continues to mature, we start to realize there are no right answers—only better and worse ones. Instead of defending right answers, our job is to generate and evaluate options.

Instead of overcommitting to our favorite idea, we invite others to ideate with us.

We visualize our thinking so that stakeholders can give us feedback, share their experience, and co-create with us. We explore potential paths to our desired outcome together.

In this world, the Hippo doesn’t always win. We win together.

Now, like every audience member listening to any conference talk since the beginning of time, I know you are sitting there thinking, “I got this.” You already do this.

Or some of you might be thinking, “This will never work with my stakeholders.”

I know it’s easy to think that you are already doing everything you can. That your stakeholders are the problem. It’s easier to blame someone else rather than to look at what you might change.

So let’s walk through an example of what it looks like to generate options, showing your work along the way, so that you can co-create with your stakeholders and discern the better options from the worse ones together.

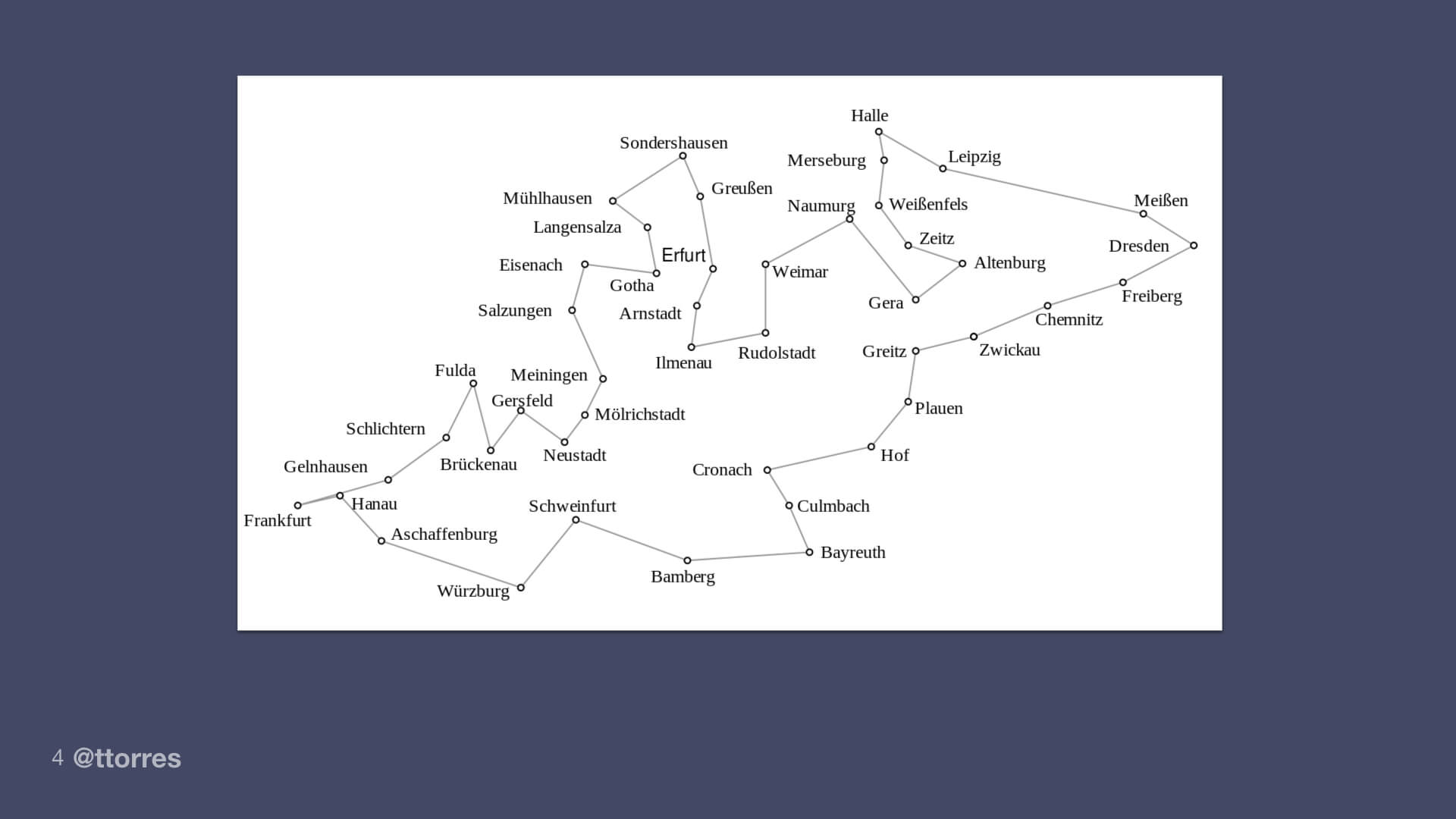

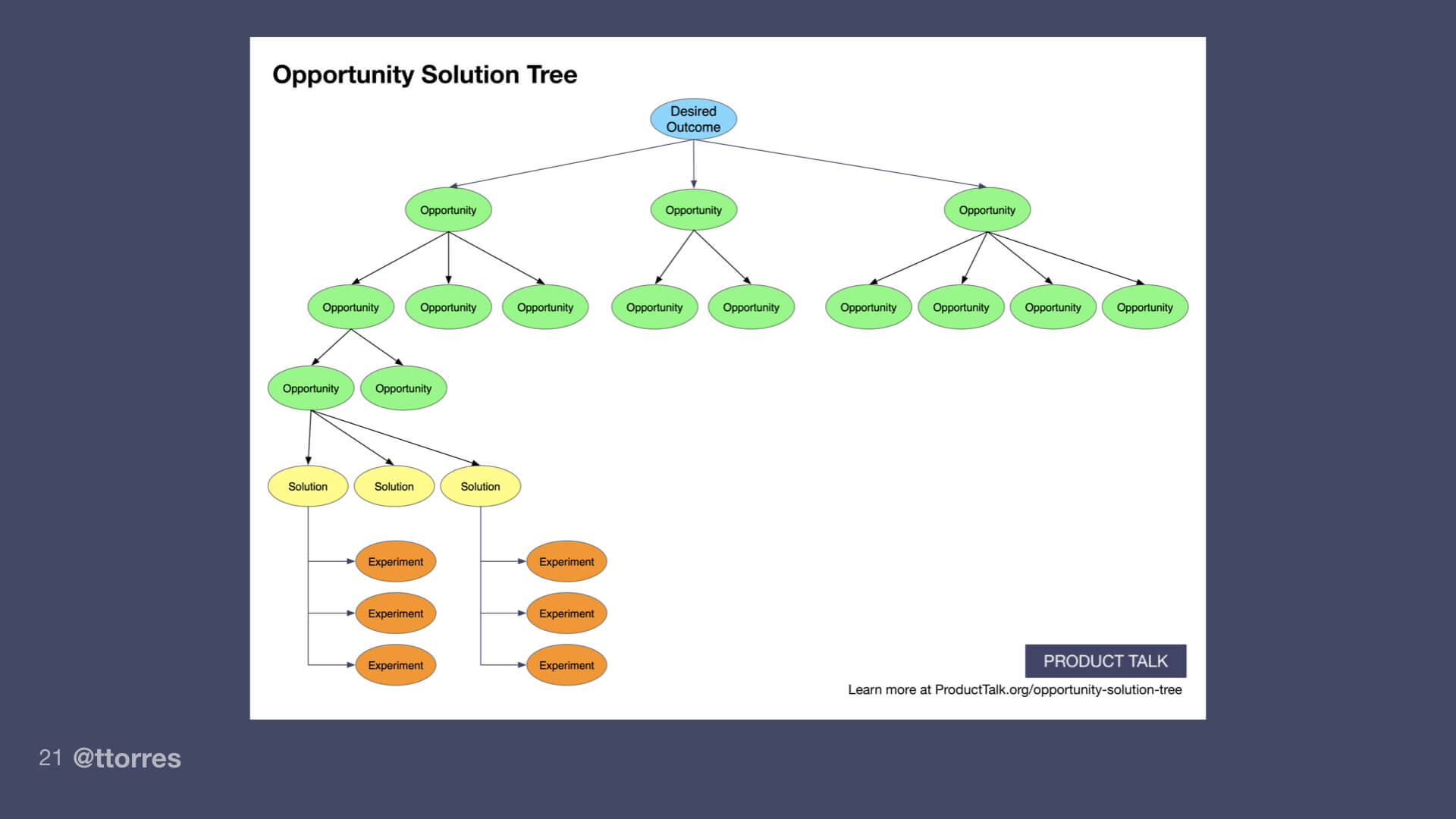

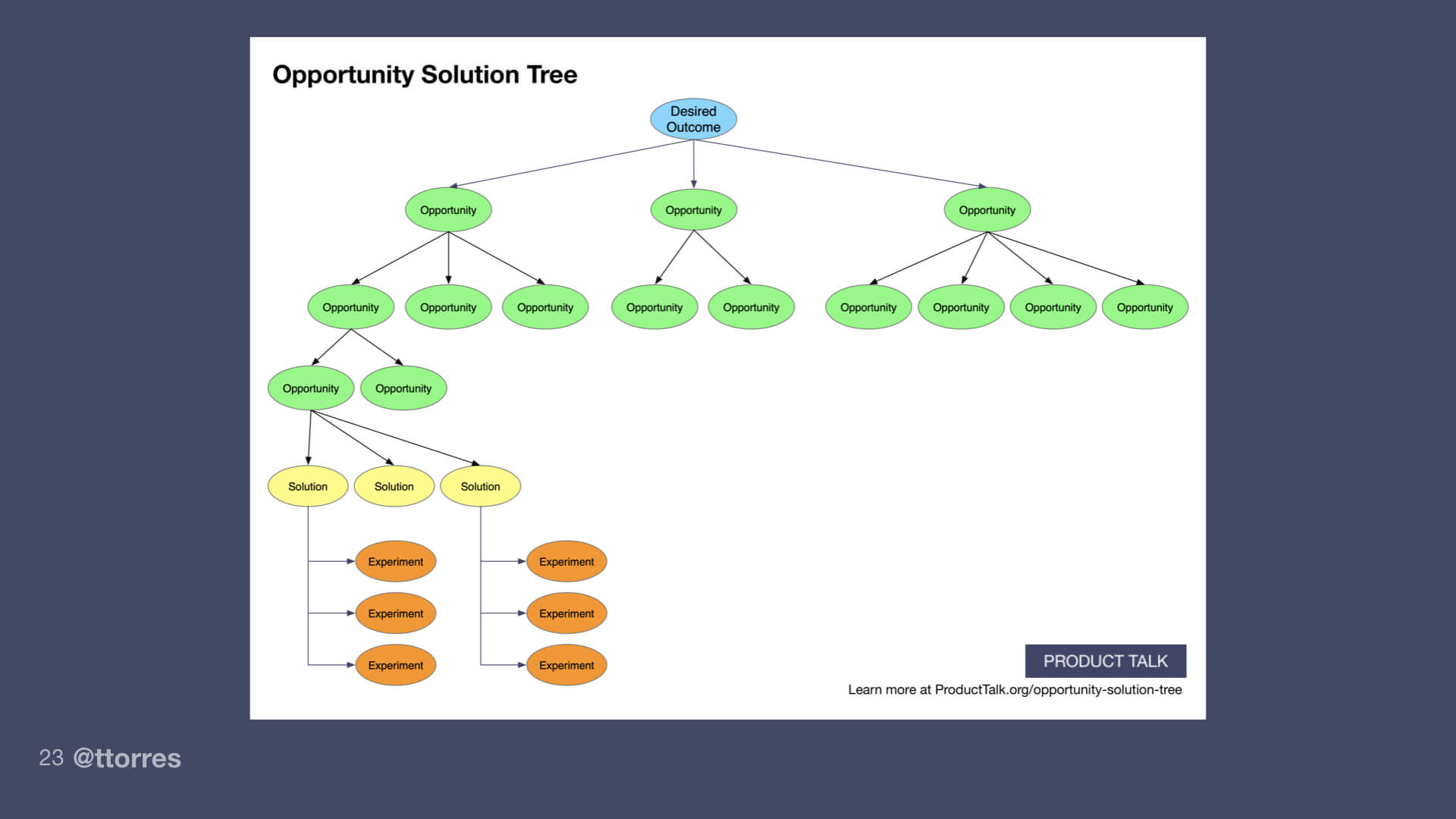

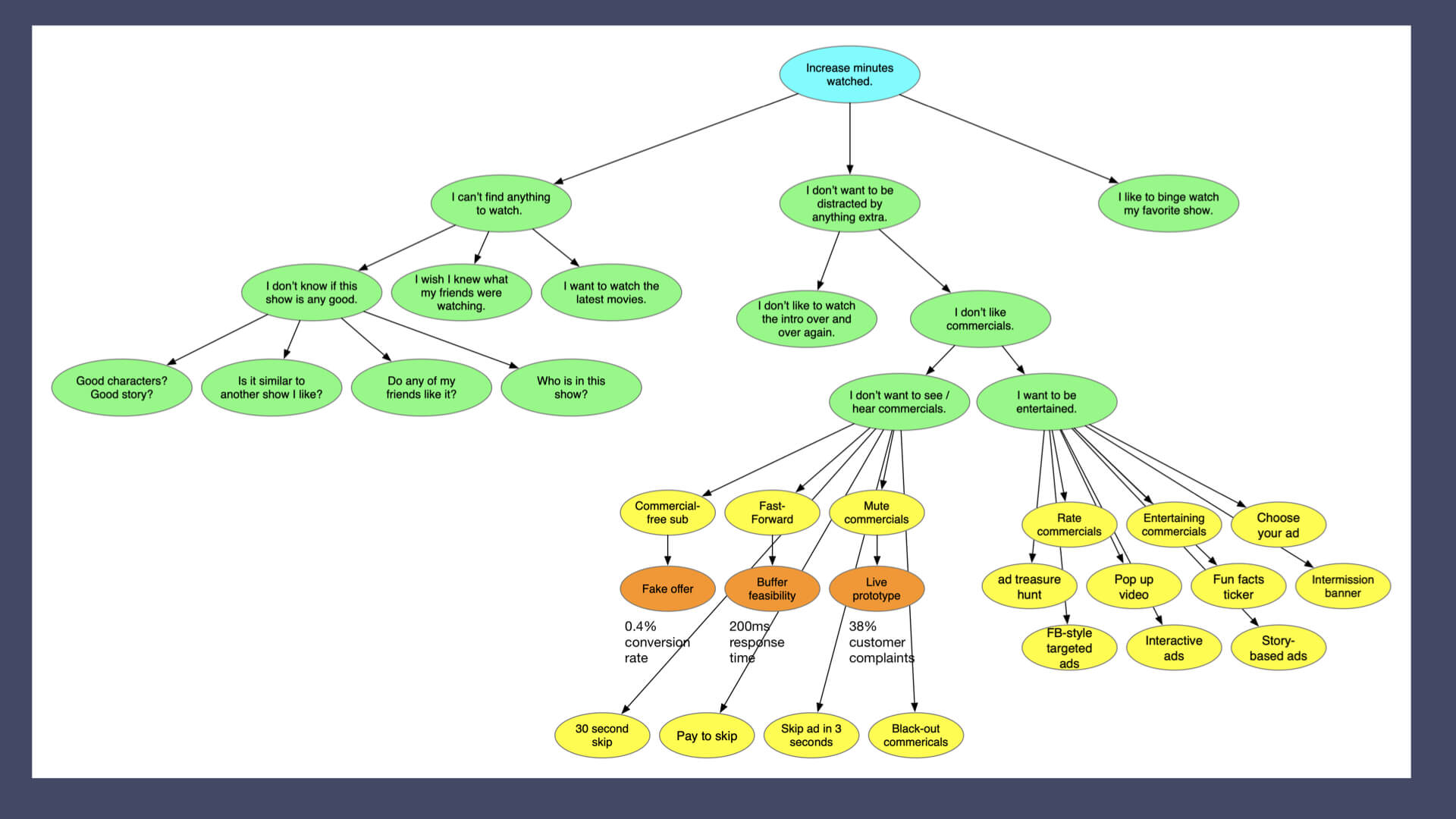

It starts with visualizing your thinking. I like to use an opportunity solution tree. This is a tool that helps you explore potential paths to your desired outcome. But I’m not dogmatic about which visual tool you use. If you have another tool that you like to use, use that. The key is to visualize your thinking so that it’s easy for others to understand.

If you aren’t familiar with opportunity solution trees, let’s review how they work.

First, we need to focus on outcomes, not outputs.

When we advocate for outputs like new features and functionality, we are focused on the right answer in a world without right answers.

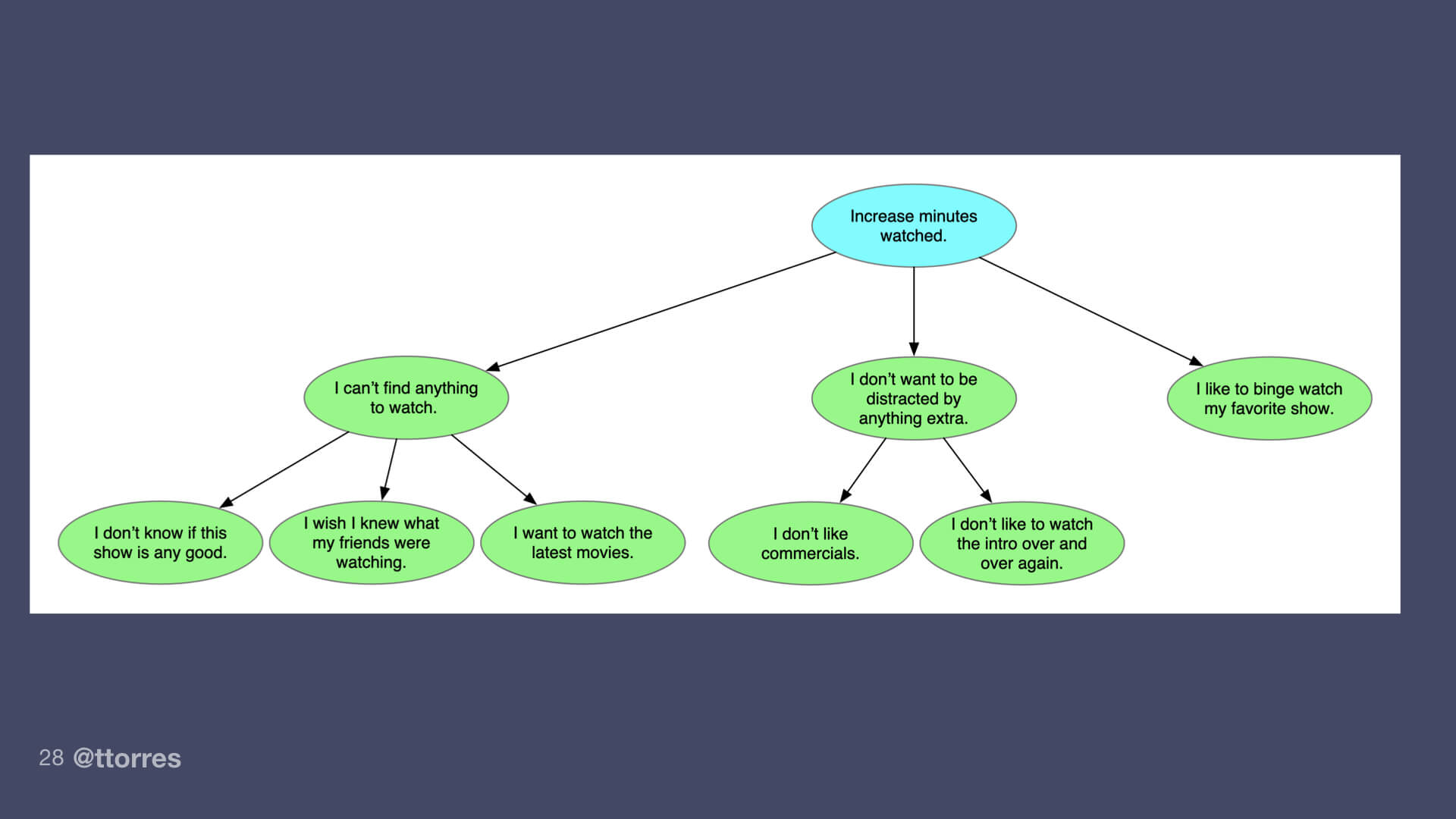

We need to work with our stakeholders to set outcomes that will create the most value for the business. In our Netflix example, this might be to improve subscription retention or increase minutes watched. That’s the blue oval at the top.

Next, we need to map out the opportunity space. That’s the green ovals.

If we are truly human-centered, we don’t want to just focus on the business outcome. We also need to work to understand our customers’ needs, pain points, desires, and wants. I collectively call these opportunities. They are opportunities to improve our customers’ lives.

I see more and more teams talking about opportunities, starting by defining the problem they want to solve. But too often, we jump to the first opportunity we identify. We hear about a problem and we immediately want to solve it.

But this is a symptom of assuming there are right answers. We assume we need to identify the one thing to build next. The one problem to solve.

Remember, the problems we work on are complex. There are no right answers. We need to discern the better ones from the worse ones. To do that, we need to map as much of the opportunity space as we can so that we can compare and contrast which opportunities look better than others.

We need to survey the landscape, do an exhaustive search, overturn every rock.

We need to remember that John Dewey, an American educational philosopher from the turn of the 20th century, advises, “To maintain the state of doubt and to carry on systematic and protracted inquiry—these are the essentials of thinking.”

Dewey is advising us not to jump to conclusions. To instead maintain a state of doubt, to doubt our first opportunity or first solution. To carry on a systematic and protracted inquiry, to generate many options, so that we can make a better decision.

This is what allows us to bring options to stakeholders rather than right answers that they are likely to disagree with.

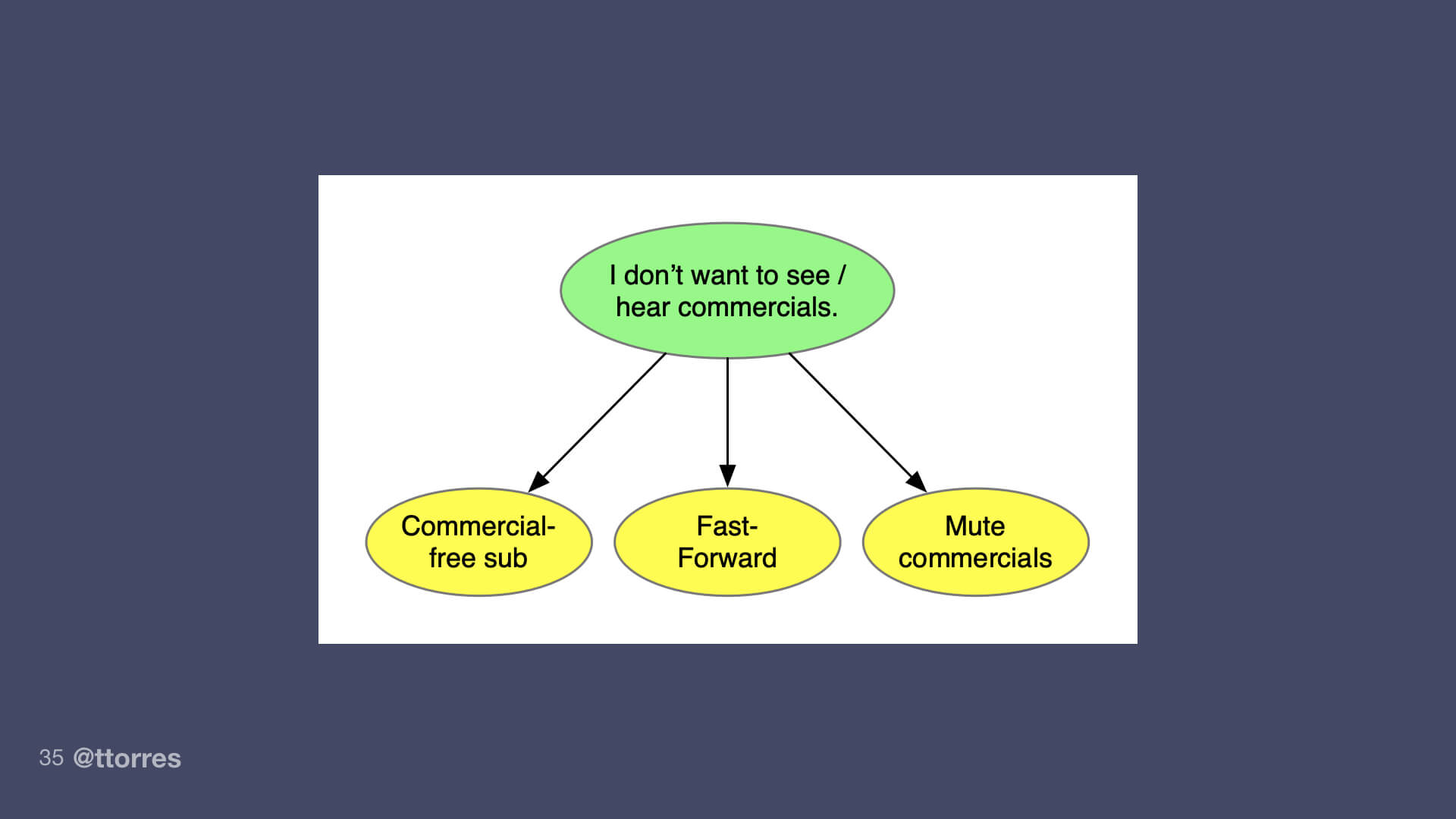

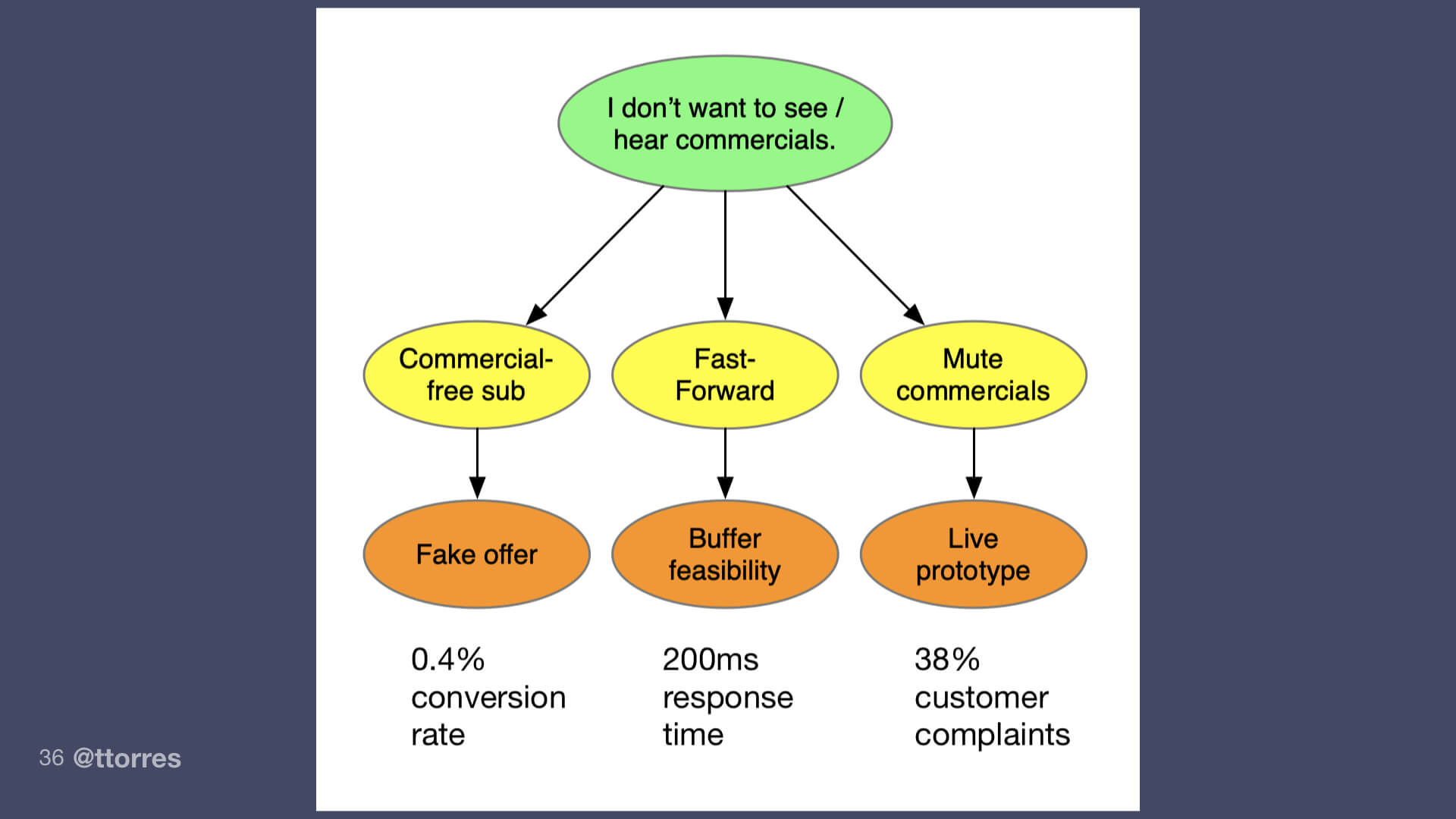

And finally, we can use opportunity solution trees to highlight what solutions we are exploring—those are the yellow ovals—and what experiments we are running to evaluate those solutions. Those are the orange ovals.

Unlike a feature-based roadmap that shows the single road you will take, an opportunity solution tree is a true roadmap, showing the many roads you might take.

When you show a feature roadmap to your stakeholders, their only option is to agree or disagree with your route. When you show an opportunity solution tree to your stakeholders, you can discuss which route to take. Your conversation is about reaching the desired outcome, not about building the right feature or addressing the right opportunity.

Let’s return to our Netflix example to further illustrate how opportunity solution trees can help you show your work.

Suppose we just agreed our desired outcome is to increase minutes watched and we now need to map out the opportunity space.

You now know that we want to conduct a continuous search to avoid rushing to a right answer. How do we do this? Where do opportunities come from?

The best way to find opportunities is to collect specific customer stories.

Too often we think about interviewing as a way to validate our ideas. This is a symptom of looking for the right answer. When we ask our customer if they like our idea, we are asking, “Did we get it right?"

Interviewing isn’t about finding the right answer. It’s about need finding. It’s about discovering opportunities.

When you ask your customer to tell you a story about a specific instance, opportunities start to emerge.

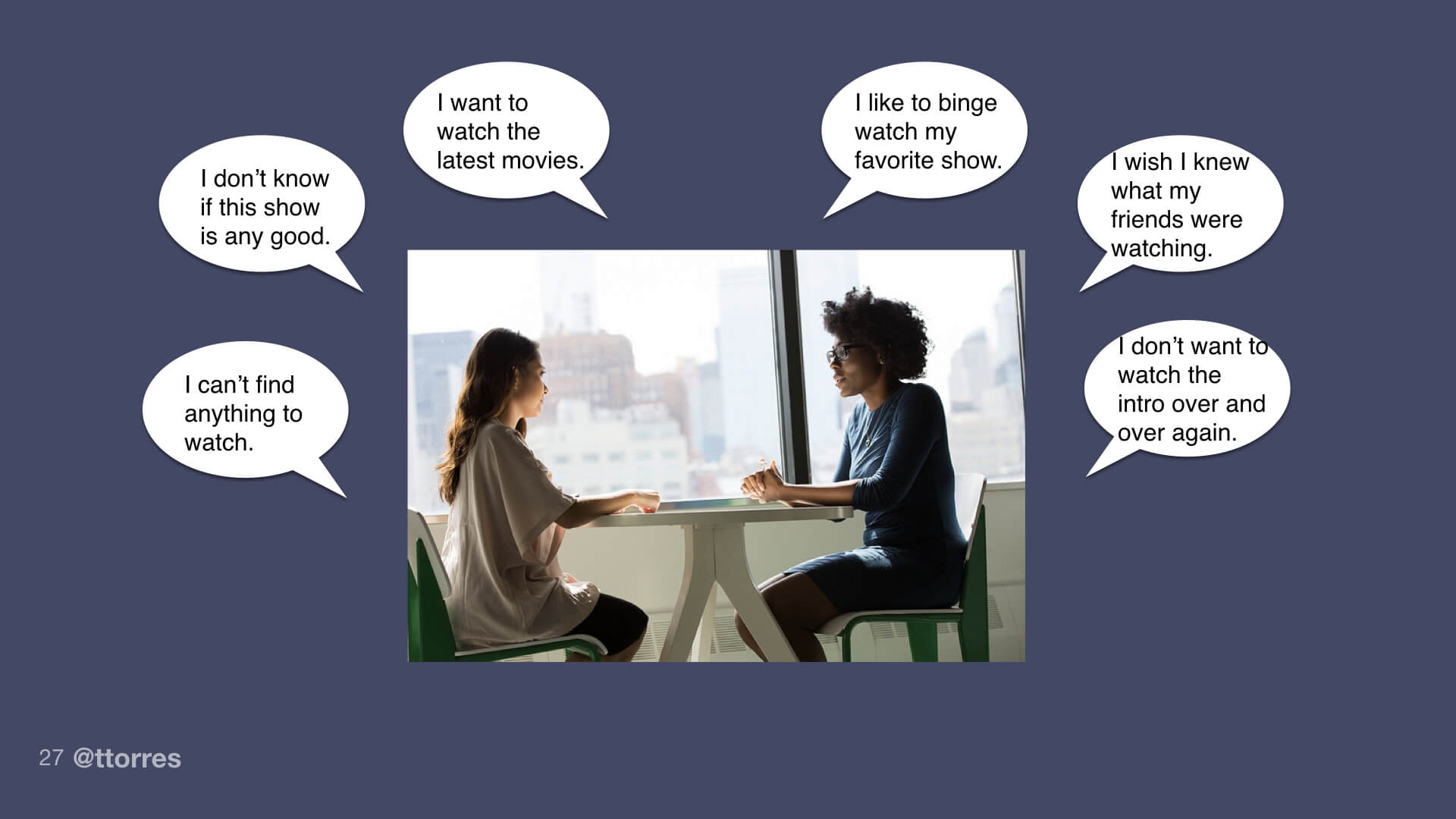

For example, imagine I asked Netflix customers, “Tell me about the last time you watched Netflix.” Notice how I’m asking about a specific instance—the last time they watched Netflix. I might hear:

“I wanted to watch Netflix after dinner last night, but I couldn’t find anything to watch.”

“I saw a commercial for Good Omens so I thought I would check it out, but I couldn’t tell if that show was any good so I passed."

“All my friends are raving about Avengers: End Game, so I tried to watch it on Netflix but I couldn't find it.”

“I just started watching Breaking Bad and I’m addicted. Last night I binge-watched four episodes.”

“I just finished Stranger Things. I hate it when I finish a show. It’s so hard to know what to watch next. I wish I knew what my friends were watching.”

“Sunday is pajama day in my house. We like to catch up on Game of Thrones. We are only in Season 2 so we have a lot of catching up to do. We usually watch three or four episodes. But it’s annoying to have to watch the intro over and over again."

Remember, opportunities are customer needs, pain points, desires, and wants. They are opportunities to intervene in your customers’ lives in a positive way.

As you collect stories, you’ll hear dozens of opportunities.

Now typically, when a team wants to share what they are learning in their interviews with their stakeholders, they try one of four strategies.

First, they share recordings of their interviews hoping that their stakeholders will listen to them. But nobody ever does. Their days are full and your research isn’t nearly as important to them as it is to you.

Second, they share their interview notes. But you guessed it, nobody ever reads them.

Third, they create a research summary deck of everything they learned. Again, nobody reads it.

Fourth, they cherry pick the research they need to support the argument they are making. Guess what. Nobody believes it.

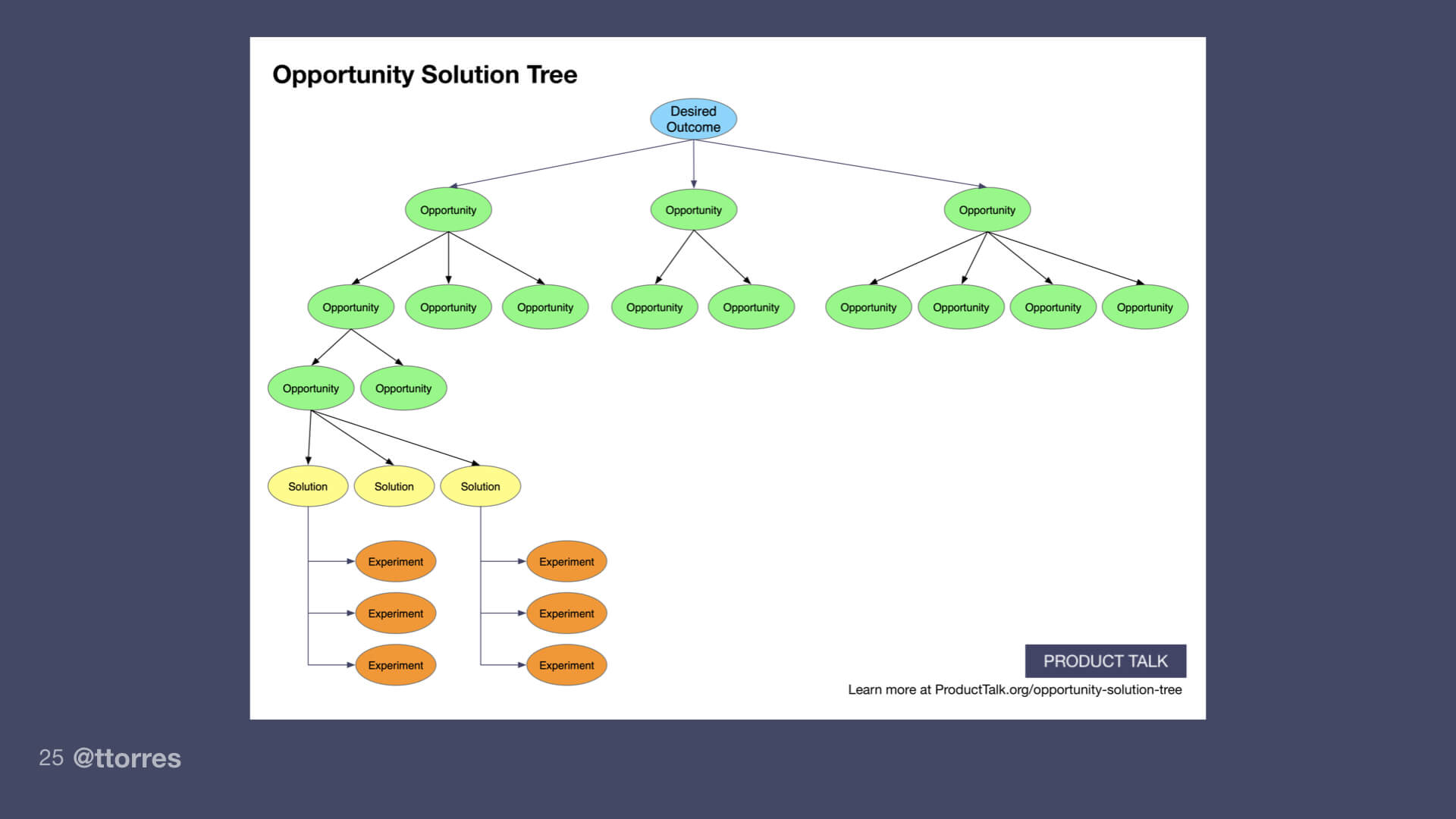

Instead, to show your work, use an opportunity solution tree to clearly communicate the opportunity space.

Don’t send it to your stakeholders and hope they read it. Meet with them and walk them through it.

Highlight the top-level opportunities that you see. Explain that across your interviews, you heard about two big challenge areas. People struggle to find something to watch and they get annoyed by all the extra stuff they have to watch. Ask them if they think you missed any opportunity areas.

Walk them through why you grouped things the way you did. Ask them if they would do it differently.

You might learn that your stakeholders have had their own customer conversations and have uncovered opportunities that you might have missed.

Stakeholders often have knowledge or expertise that we don’t have. You could imagine that a product manager working on the consumer experience at Netflix might not be aware of all of the content partner needs. Like most two-sided marketplaces, I imagine consumer needs and partner needs often come into conflict.

Our stakeholders can help us map out and better understand more of the opportunity space.

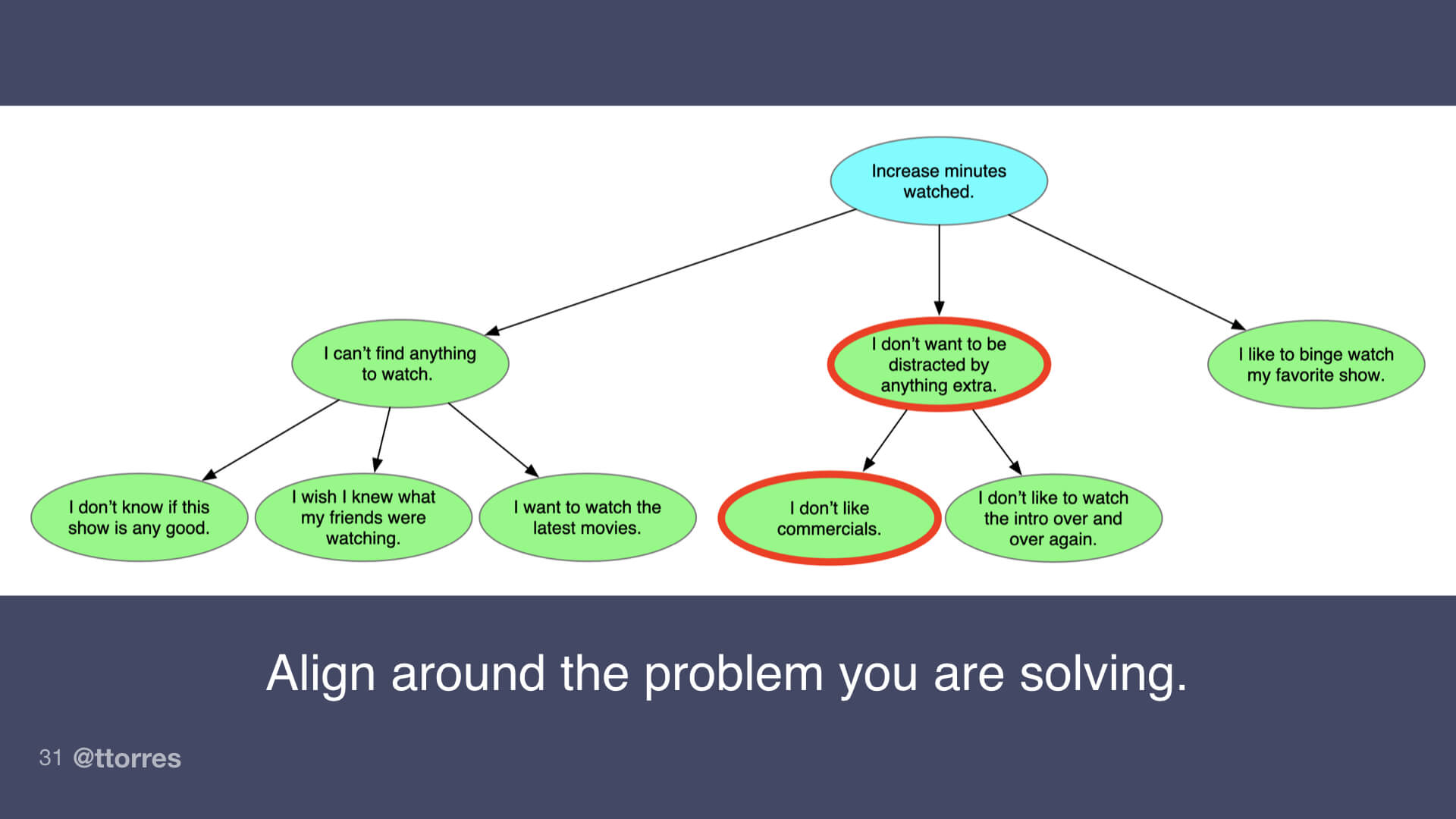

Instead of arguing about different solutions before we’ve agreed what problem we are solving, we can build the opportunity space together.

Now most of us don’t have the luxury of spending weeks mapping out the opportunity space. Nor do I recommend that you do so. We only create value when we ship code. So sooner or later we are going to have to choose which opportunities to pursue next.

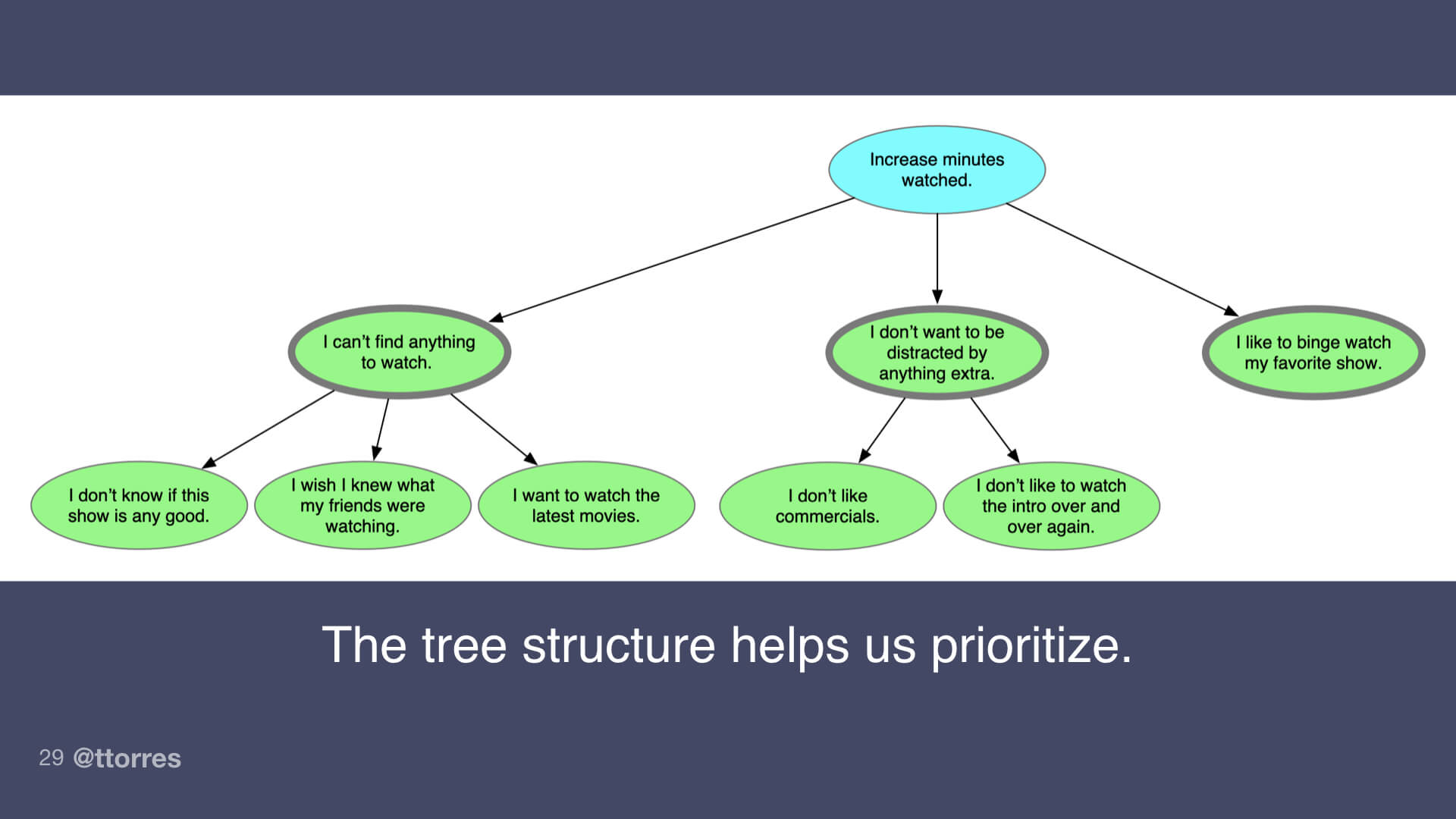

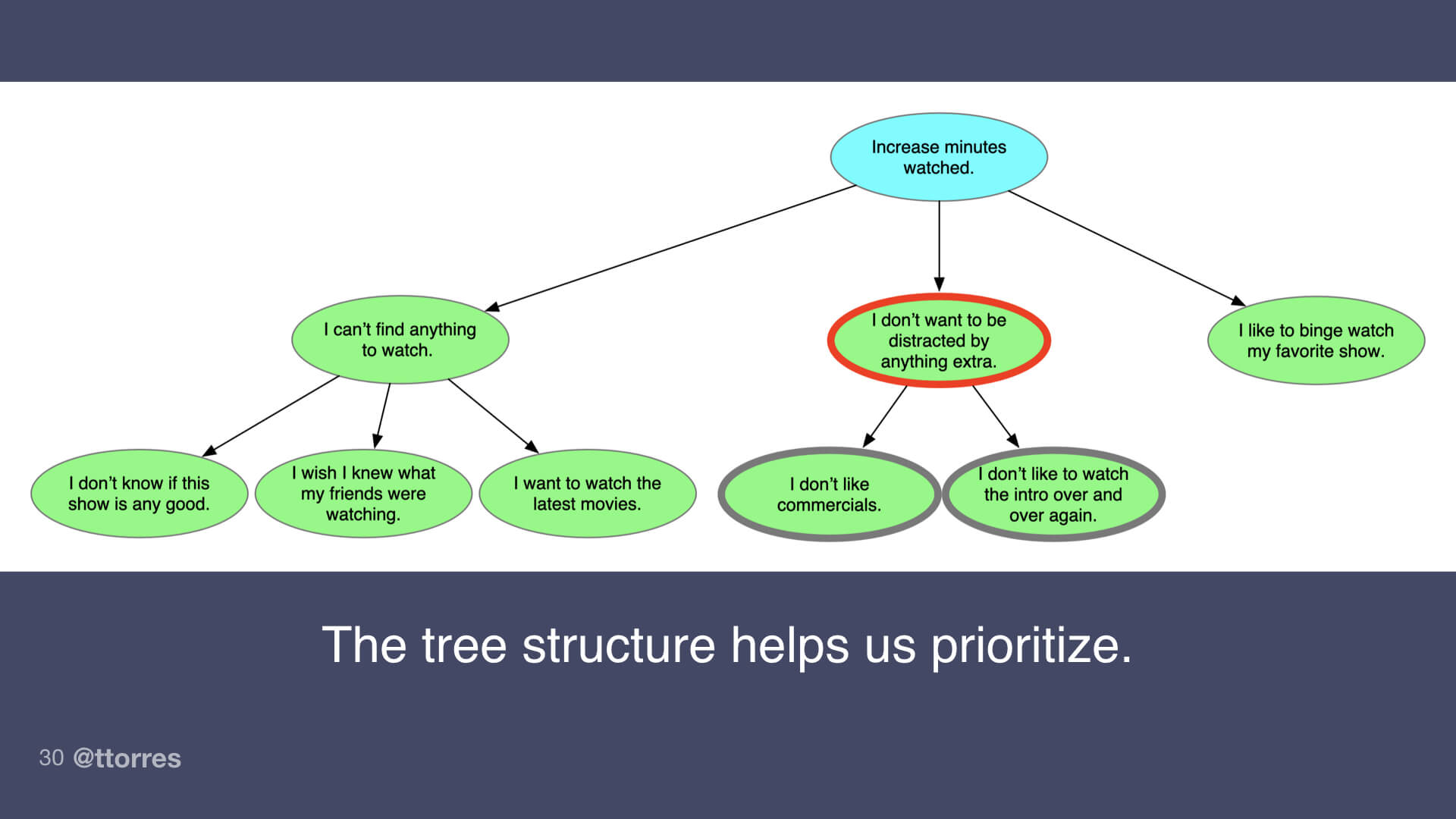

The tree structure can also help us prioritize where to focus. We can iteratively walk down the tree, prioritizing row by row. We can start by asking which of our top-level opportunities are most important.

If we decide this middle one “I don’t want to be distracted by anything extra” is our top priority, we can focus on prioritizing its sub-opportunities. We can safely ignore the rest of the tree. This saves us from having to assess every opportunity we encounter.

Choosing a target opportunity is an important decision. Notice how we don’t want to fall into the trap of believing there’s only one right answer. If all of the opportunities represent real customer needs, there are a lot of right answers. The conversation to have with your stakeholders should be about comparing and contrasting these opportunities against each other.

By using the tree to show all the options we’ve uncovered and which decisions we’ve made, we invite our stakeholders to examine our thinking. We are showing our work. If they disagree with us, we have all the other options in front of us.

This changes the conversation from the opinion battle about what to build to a more evidence-based discussion about which path looks more promising.

In this world, the Hippo doesn’t always win. We win together.

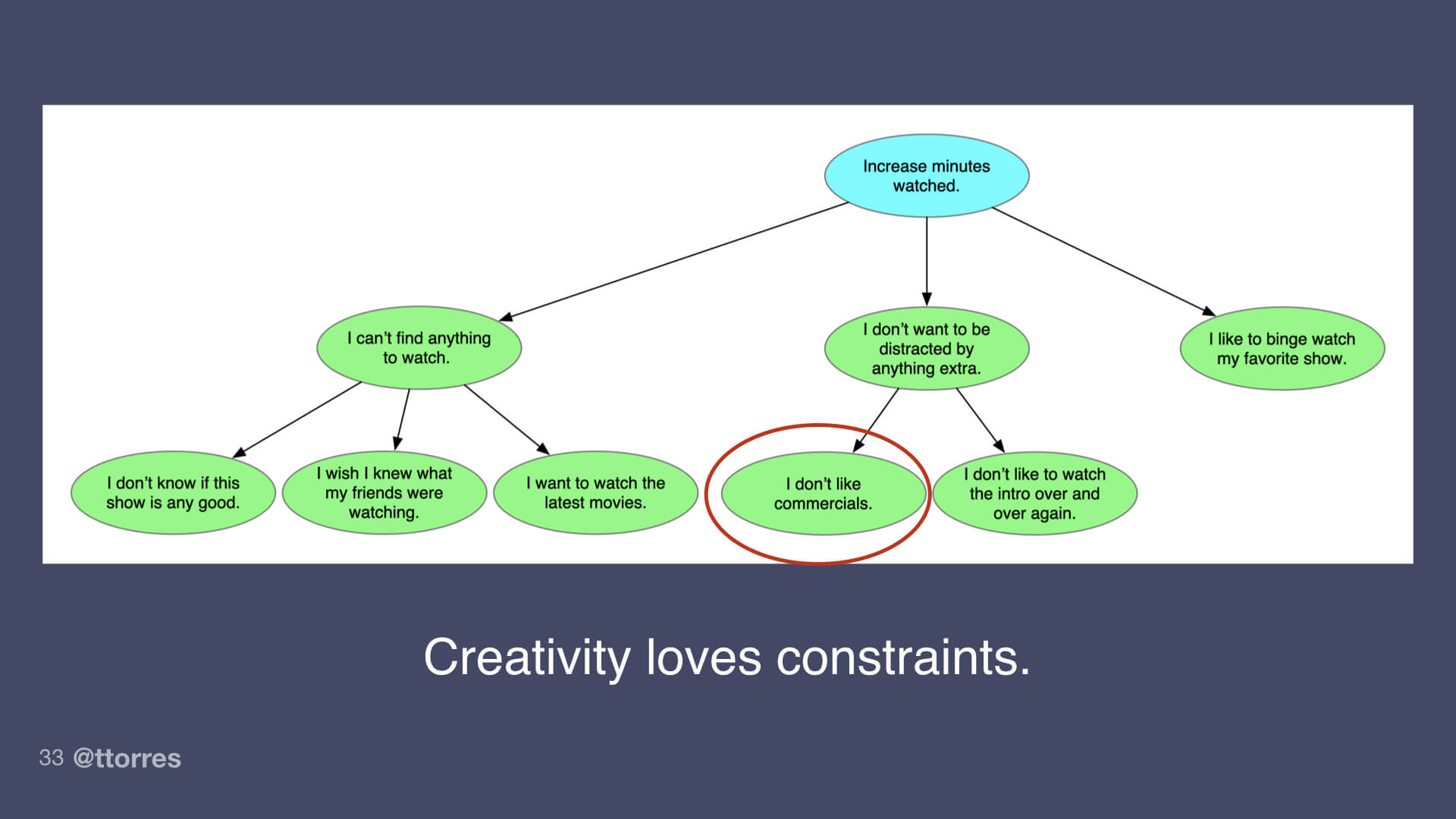

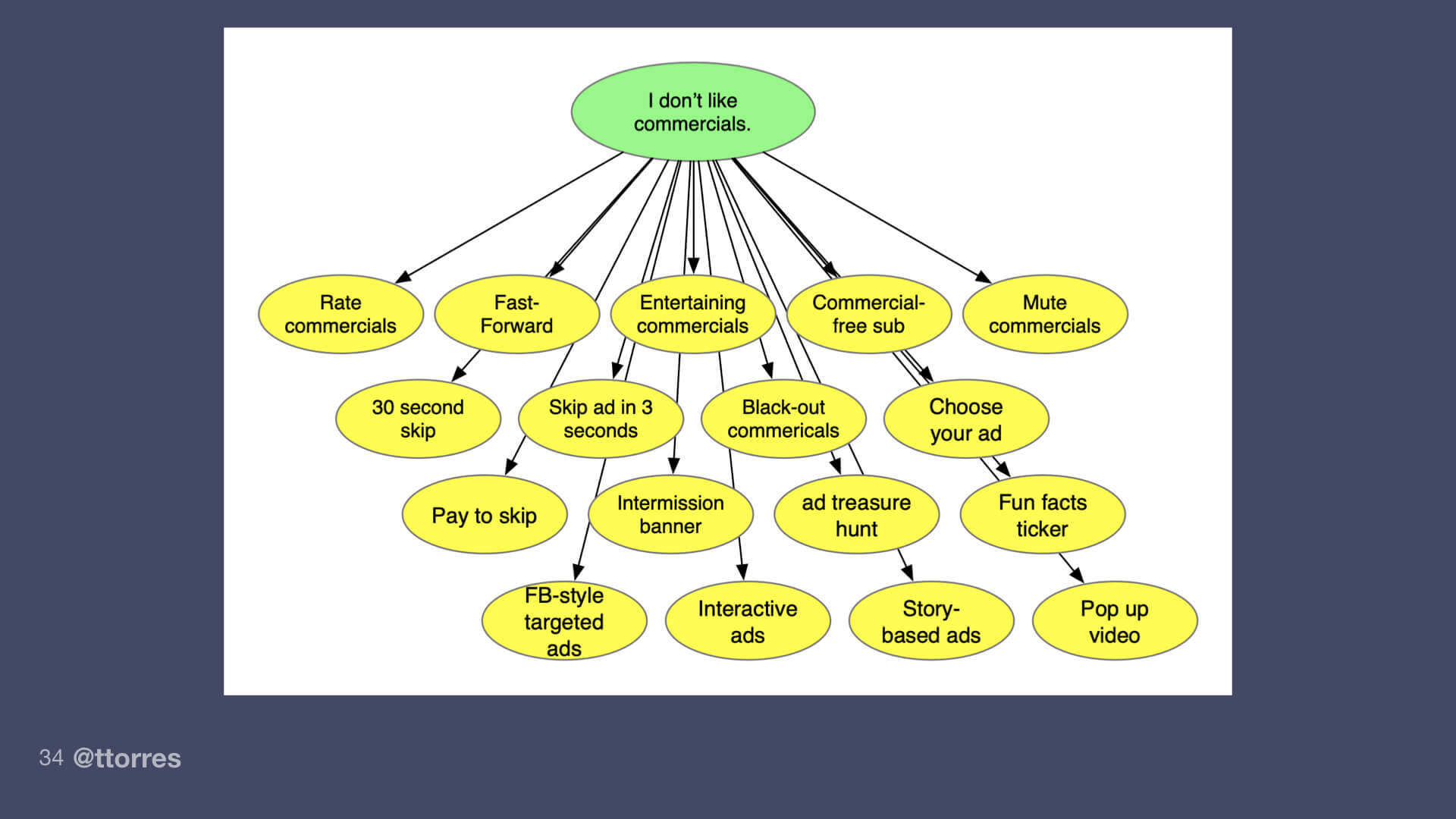

Once we’ve chosen a target opportunity, we can carry this “show your work” mindset through to the solution and experiment level.

Remember, we don’t want to revert back to the right answer. Or forget to show our work. That means we can’t just propose a single solution for our target opportunity. Our job is to generate options and to discern the better ones from the worse ones.

I advise teams to generate lots of solutions for the same opportunity. More than they are usually comfortable with. We are used to generating a lot of ideas. But they tend to be lots of first ideas across our tree of opportunities.

If you look in your backlog today, you’ll see that you have several first solutions that target lots of different needs. This doesn’t help us escape the trap of the right answer.

To get the benefit from ideation, we want to generate a lot of ideas that address the same need. Creativity research tells us that the more ideas we generate the more likely we’ll generate more diverse and novel ideas. This is how we find truly innovative solutions.

It’s also how we create options for stakeholders and avoid the endless opinion battles that we know we’ll never win.

Share all of the ideas you generated with your stakeholders. Go one step further and invite them to ideate with you. Remember, we want to co-create with our stakeholders.

When it’s time to decide which ideas to explore through prototyping and experimentation, include your stakeholders in the decision.

As you explore solutions, capture the key experiments and results right on your tree. Invite your stakeholders to interpret the results with you.

Now not all of your stakeholders are going to be able to walk through every step of discovery with you. Some will be more involved than others. Most will ignore your invites to ideation sessions and never read your interview notes. This is expected. They have their own jobs.

But when you have an opportunity solution tree supporting your conversations with your stakeholders, it’s much easier for them to get caught up on what they missed.

In one visual, they can quickly understand what opportunities you’ve uncovered, how you’ve prioritized them, what solutions you’ve considered, and where you are in evaluating them.

They can question your thinking, they can add their own thoughts, and it’s easy for them to co-create with you.

If we do our discovery well, any of the paths on our tree are a potential path to our desired outcome. Our conversations with stakeholders are less about our final answer and more about exploring options.

This gives your stakeholders an easy way to engage and contribute and you’ll get much better feedback along the way. You’ll be surprised at how reasonable those Hippos become.

So remember, stop fixating on the right answer.

Show your work.

Focus on discerning better options from worse ones.

Give it a try and let me know how it goes.

Thanks everyone.

One last note: I was informed before going on stage that I could take more time than was originally allotted. As a result, I expanded the summary to include more about my personal experience with this journey from rushing to the right answers to learning to show my work to learning to generate and evaluate options.

I shared that I still struggle with fixating on the right answer. That I catch myself doing this every day.

In this section of the talk (as given, not written), I encouraged everyone to stop fixating on the right answers. I justified this by arguing, “You are not one feature away from success and you never will be.”

This was by far the most tweeted line of the talk. Once I have access to the video, I’ll expand this blog post to include more of the summary as given, including that line.

Comments ()