Writing a Book: How Continuous Discovery Helped Me Write a Better Book

It won’t surprise you to hear that I use the same continuous discovery habits that I wrote about in my book to run my business.

My primary objective across my business is to increase the number of product trios who adopt a continuous cadence to their discovery work.

When I set out to write my book, I was focused on a specific opportunity: “I’m not sure what discovery tactics to use when.” I had heard from many teams who were adopting discovery tactics, but were getting lost amid the messiness that is discovery. They didn’t know what tactics to use when. They weren’t sure which methods were good for which steps in the process and they wanted a framework for putting it all together.

This need is what led me to think about and design the opportunity solution tree. I wanted to give teams a structure that could guide their thinking—that could help them sort through the mess.

When I finally wrote about the opportunity solution tree (back in 2016), I knew that it was a big enough idea that I would need to write a book about it. And thus, I announced that I was in fact writing a book. That was a mistake.

The Waterfall Nature of Books

I started to write my book and immediately got stuck. Some of it was normal first-time author insecurity. I wondered, “Can I write a good book?”, “How will I know if it’s good?”, and “How do I know my advice works?”

And that’s when I realized that book publishing is the epitome of a waterfall process. You write everything upfront, release it, and hope it resonates with the reader. I wasn’t willing to hope. I didn’t want to spend a year writing a book that nobody needed.

I know many authors who use their blog as a way to test content. That was a start. But blog analytics (views and shares) don’t track impact. I wanted to know if my advice was changing behavior in a way that led to better results. I had no visibility into what impact my content was having on teams after they read it.

So I put the book on hold and started devising a plan to test my content.

Turning My Content Into a Product

Fortunately, I was actively coaching several teams. I knew that my coaching was having an impact. My primary question was if my content would work without the coaching.

So I started to experiment. First, I shifted my coaching to a “flipped classroom” model. I started codifying what I taught in an online curriculum. Each week, my teams worked through the content on their own, did an activity that was designed to test how well they could apply the content to their own work, and then came to their coaching session. During our coaching session, we reviewed their work and iterated on it as needed. This gave me a great feedback loop to measure the efficacy of my content.

My schedule allowed me to track that efficacy by cohorts. I had set up my schedule to coach in bursts with lots of time off in between bursts. I originally designed this schedule to accommodate my introverted nature and to give me plenty of time to think, read, and write. But it had another benefit. Because I worked with three sets of ten teams over the course of the year, I could look at each set as its own cohort and track progress cohort over cohort.

I started measuring the pace at which each team moved through the curriculum. Some teams got stuck because they couldn’t find customers to interview. So I started to ask, “How can I make it easier to interview than to not interview?” That led to me developing the recruiting automation tactics that I wrote about in the book.

Some teams would get stuck on opportunity mapping. I knew mapping the opportunity space is one of the toughest activities in the process that I teach, but I also knew the benefits made it worth it. So I iterated on how to simplify it, how to scaffold the process, until teams learned each of the key skills—identifying opportunities, opportunity framing, experience mapping, grouping and structuring opportunities.

Many teams hit a snag when it was time to test assumptions. They’d get bogged down for weeks trying to run a single assumption test. That forced me to ask, “How can I simplify this?” I started to look for the most common ways of testing assumptions and the simplest infrastructure that needed to be in place to make that happen.

I kept tracking the pace of teams in each cohort. And with time, the content got better. Teams were able to do more on their own. Instead of having to teach during the coaching hour, we refined and went deeper.

By the end of 2019, I realized that most of my teams were able to get started on their own. Coaching was a nice-to-have that accelerated their progress and allowed them to develop advanced skills. But the content was strong enough to get a team through the basics on their own.

And that’s when I knew it was time to write the book.

Learning How to Write a Book

I sat down to write the table of contents and was amazed by how easy it was. The structure of my book would match the structure of my coaching curriculum.

I decided to write the Continuous Interviewing chapter first. I had iterated on this content the most and thought it would be the easiest chapter to write. I was wrong.

I knew my readers wouldn’t have the luxury of asking their questions during a coaching session, so I tried to address everything they might ask. When I was done, I was on pace to write a 750-page book. My strategy wasn’t working.

I knew my content was good, but I didn’t know how to convey it in book form. I knew I needed more feedback.

I posted an excerpt from the chapter as a blog post and got some brutal (but necessary) feedback that my writing was long-winded and repetitive. I was struggling to find my book voice and this feedback helped me realize my book voice and my blog voice were one and the same.

Jeff Merrell, my co-instructor at Northwestern, suggested that I was burying my lede. By trying to answer every potential question, I was losing the heart of the narrative. I ruthlessly cut everything that wasn’t necessary.

Over the next several months, I wrote a few more chapters. But it still felt like I was flying blind. I knew from coaching that the content was good. But I was still struggling with how to turn it into a book.

So I added another feedback loop.

Continuing to Test and Iterate as I Wrote the Book

In May, I launched my Early Readers program. I invited 60 people to read chapters as I wrote them. A handful of them had been through my coaching program, as I wanted them to give feedback on what I was leaving out. But most were new to the content.

Each month, I released one chapter and then hosted calls where readers could give feedback. I focused specifically on what people were able to put into practice. I wanted to know if reading the book inspired them to act.

My Early Readers gave invaluable feedback. They encouraged me to add more customer stories. They asked for common mistakes to avoid, which led to the “Common Anti-Patterns to Avoid” sections that you find at the end of most chapters. They told me when chapters didn’t work and read rewrites until I got it right.

My Early Readers helped me iterate on how to convey the content in book form.

Working with Reviewers: The First Full Manuscript Judgments

One of the last stages of writing a book is inviting reviewers to comment on the full manuscript. I asked five people to review the book—two were partners who were well-versed in my content, two were thought leaders in the space, and one was an avid reader who had built a strong community of technology executives.

This was the first time anyone was reading the book cover to cover and I anxiously awaited feedback.

The first reviewer who responded offered positive feedback, but also suggested that the book still needed a lot of work. Their primary concern was my reliance on research. They thought that instead of drawing from academic studies that instead I should rely on stories from my own experience.

At first, this feedback gutted me. The research was important to me. I didn’t want to write yet another thought leader book on how to do product management. I wanted to write a book that synthesized what we know from research with what we know from practice. I had plenty of both to draw from.

I stewed on this feedback for days. I bounced the feedback off a few people that I trust. I asked my Slack community. My editor reminded me that I needed to write the book that only I could write (and that included research). But I still wasn’t sure.

And that’s when I reminded myself who I was writing this book for—product managers, designers, and software engineers who want to serve their customers. I needed to know what they thought.

So I polled my Early Readers. I explained that one of my reviewers suggested I remove the academic research from my book and asked them to choose one of the following responses: “I agree, the research doesn’t do anything for me,” “I like some research, but you’ve used too much,” “I like some research, but it’s not actionable enough,” and “Keep the research.” Overwhelmingly, people responded with “Keep the research.”

A few people responded with “I like some research, but you’ve used too much” or “I like some research, but it’s not actionable enough.” I followed up with each and every one of them.

Based on their feedback, I completely rewrote the second chapter. Throughout the book, I simplified descriptions of studies. I moved a couple of items to the footnotes. But I did not water down the research. Instead, I did my best to make it more accessible and more actionable.

The book is better as a result of this feedback.

The rest of my reviewers also provided great feedback. One even asked for more research. It helped me see that no book (just like no product) can be everything to everyone.

I finalized my manuscript knowing that I wrote the best book I could write and knowing (thanks to my Early Readers) that there was an audience for it.

Underestimating the Effort to Publish a Book

With a final manuscript in hand, I thought it would be a matter of weeks before I could launch the book. When I learned otherwise, I laughed at myself. I made the classic product manager mistake—I underestimated the delivery effort required to produce a book.

I knew I still had to create a cover design and interior design, work through final copy editing revisions, ebook formatting, and make distribution and pricing decisions. I just didn’t know how much work each of these steps would entail.

I hired an agency to help produce the book. This was incredibly helpful because I had never published a book and I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

However, it also meant that I was one degree removed from the creative work. I never met the designer that worked on my cover design. Instead, my feedback went through a project manager. As a product manager and designer, this was hard for me. I wanted to have a conversation about the design and iterate on it together. I ended up hiring my own designer to finalize the design.

My blog editor Melissa edited each chapter as I wrote them, so I wasn’t expecting a lot of back and forth with the copy editor. And to Melissa’s credit, there wasn’t much, but there was more than I expected. I spent more time thinking about whether it was “continuous discovery habits” or “continuous-discovery habits” than I ever thought I would. I went with the former because “continuous” modified both “discovery habits” and “continuous discovery” modified habits. The title had a double meaning—our discovery habits should be continuous and continuous discovery relies on good habits.

I continued to rely on my feedback loops throughout this process. My Early Readers gave feedback on cover designs. I polled my Twitter followers about where they bought books and what formats they purchased. I loved how fluid and collaborative the process was from start to finish.

Managing the Uncertainty of Launch Day

Like many product releases, it was hard to put a launch date on the calendar. I had no idea how long it would take to complete many of the production steps.

In January, with the final manuscript in hand, I announced the book would come out in late spring or early summer. I was optimistic that we might beat that timeline. But I didn’t want to over promise.

I started to worry when the cover design took way longer than I expected. Throughout the production process, I had time estimates from my agency on how long different steps might take. But some of them went much faster than expected and others took way longer than expected. It was impossible to choose a date.

I knew that the paperback would be ready first. We didn’t even start on the ebook formatting until after the printer files were finalized. And I hadn’t even started thinking about the audio version. So I thought I would release each format as they became available—in a truly Agile and iterative way.

But it wasn’t clear how long print distribution would take. And the ebook formatting went much quicker than I thought. By mid-April I finally found myself ready to launch the paperback and the ebook much sooner than I thought.

There was only one step left. I needed to order author copies and sign off on the paperback versions. There was only one problem: I was heading out on a two-week mountain biking road trip and shipping times were wildly inconsistent.

Even though everything was ready to go, my launch date was still uncertain. I circled May 19, 2021 as my tentative launch date and left for my vacation hoping my author copies would be sitting on my doorstep when I returned.

Thankfully, this last step went exactly as planned. The copies were waiting for me when I got back and both copies (the Amazon print-on-demand version and the IngramSpark version) looked great. All that was left was to wait for launch day.

Launch Day Finally Arrived

On May 19, 2021, we launched paperback, Kindle, and ePub versions of Continuous Discovery Habits around the world.

I had no idea what to expect. I was blown away by the response. I spent all day reloading Twitter and LinkedIn, watching as excitement spread about the book.

Marty Cagan posted the following to both LinkedIn and Twitter:

It made my morning.

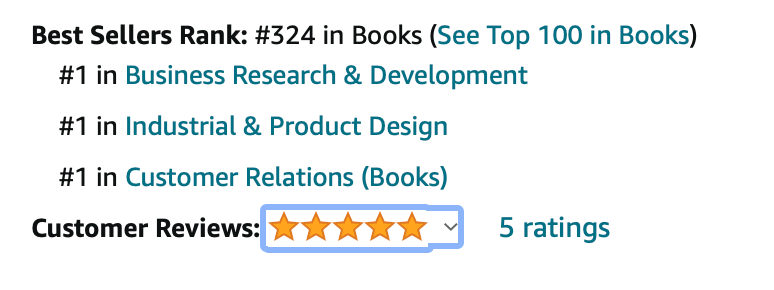

At one point, we were in the top 325 books sold on Amazon.com that day (in any category)!

I was giddy.

Over the past two months the sales, reviews, and ratings have been rolling in.

A publisher told me that a successful non-fiction book sells 10,000 copies over its lifetime. Continuous Discovery Habits has sold 10,000 copies in the first two months. Wow!

Over 150 people have rated the book on Amazon and here’s what some of the reviewers have said:

“I love Teresa’s approach because it’s practical, action-oriented, and effective.” - Aaron Briggs

“A lot of product books and blog posts I read stay high level. With some, you feel like you've read a content marketing piece that's meant to sell a workshop. This book feels like it IS the workshop. Teresa doesn't hold back.” - Guy Peled

“I have read many books on product management, but Continuous Discovery Habits is the only book that I have read that makes it easy to put the advice into action. Filled with great advice, this is a MUST read for any product manager, product designer, and engineering team lead.” - Benjamin Perelman

“While I knew it would be valuable, I didn’t realize how clear and actionable Continuous Discovery Habits would be. The information is so thoroughly presented with so many bits and pieces that you can immediately start integrating into your own practice. It’s clear that Teresa not only knows what she’s talking about, but is realistic about how product organizations actually work and the idiosyncrasies associated with them.” - Meighan

People continue to share their thoughts on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Goodreads, and I hear from companies every day who say their product teams are reading it together.

My favorite feedback is when readers tell me they are putting the habits into practice. After all, that’s why I wrote the book.

How You Can Help Keep the Momentum Going

If you want to help get Continuous Discovery Habits into more hands, here are a few things you can do:

- Write an Amazon review. 84% of my book sales come from Amazon and reviews impact search rankings and help buyers decide if the book is right for them. Your review has a massive impact. If you rated the book on your Kindle, sadly this doesn’t propagate to Amazon. So please review it again there.

- Share your thoughts about the book on social media. Every time someone posts about the book, some people hear about it for the first time. Word of mouth is a primary driver of book sales.

- Recommend it to your friends, colleagues, or book club. Most people choose books based on trusted recommendations. Do you know someone who might benefit from the book? Recommend it to them.

- Bring me in to speak at your company, your meetup, or host me on your podcast. As part of my virtual tour, I’m doing corporate talks, community events, and podcast interviews. Reach out if you’d like me to join your event.

In my wildest dreams, I couldn’t have imagined that the book launch would go so well. I knew many of you were anxiously awaiting the book, I just grossly underestimated how many of you there were.

I wholeheartedly want to thank each and every one of you for helping to make this book a success. This is only the beginning. There’s much more to come.

Comments ()