Have you heard? My new book Continuous Discovery Habits is now available. Get the product trio's guide to a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery.

Have you heard? My new book Continuous Discovery Habits is now available. Get the product trio's guide to a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery. I recently asked a woman what factors she considered when buying a new pair of jeans. She didn’t hesitate in her answer. She said, “Fit is my number one factor.”

That seems reasonable. It’s hard to find a pair of jeans that fit well.

I then asked her to tell me about the last time she bought a pair of jeans. She said, “I bought them on Amazon.”

I laughed and asked, “How did you know if they fit?”

She said, “I didn’t, but they were a brand I liked and they were on sale.”

What’s the difference between each of her responses?

Her first response tells me how she thinks she buys a pair of jeans. Her second response tells me how she actually buys a pair of jeans.

She thinks she buys a pair of jeans based on fit, but brand loyalty and price (or getting a good deal) were more important when it came time to make a purchase.

The Gap Between What You Think You Do And What You Actually Do

This story isn’t unique. It’s not unique to the person I was talking to, nor is it unique to buying jeans.

I often use this example in talks and workshops. But instead of telling the story, I illustrate it by asking someone in the audience the same two questions.

The purchasing factors often vary, but there’s always a gap between their first answer and their second answer.

Other scenarios work as well:

- Ask someone how often they go to the gym, then ask them how often they went last week.

- Ask someone about their diet, and then ask them about their last three meals.

The examples are endless.

We rarely take the time to understand our own behavior. But if asked, we don’t hesitate to give an answer. – Tweet This

There are a couple of factors at play here.

First, we tend to respond to questions about our behavior based on our ideal view of ourselves.

We intend to buy jeans based on fit. After all, that’s pragmatic. But we get hooked on the lure of a good deal or the ease of online shopping.

We’ve all had this experience. We know that we don’t often live up to our ideal selves. It’s why New Year’s resolutions are so problematic and why we pay for gym memberships that we don’t use.

We tend to respond to questions about our behavior based on our ideal view of ourselves. – Tweet This

And second, our brains are exceptionally good at creating coherent (but not necessarily true) stories that deceive us.

This second factor can be harder to accept. Many of us pride ourselves on being logical, rational beings. How can it be that our brains regularly deceive us with coherent stories that simply aren’t true?

This is such an important factor that I’m going to spend a large amount of this article illustrating it.

Our brains are exceptionally good at creating coherent (but not necessarily true) stories that deceive us. – Tweet This

Your Brain Excels at Deceiving You

Michael Gazzaniga, a neuropsychologist, conducted a phenomenal study that shows just how effective our brains are at deceiving us.

He worked with split-brain patients—patients who underwent a medical procedure to sever the connection between the right and left hemispheres of the brain in an attempt to control severe seizures from moving from one hemisphere to the other.

To understand this study, we first need to review some facts about the brain.

First, the left and right hemispheres are each responsible for different functions within the brain. The brain coordinates these functions with communication between the two hemispheres. Because split-brain patients have had the connection between their two hemispheres severed, no such communication or coordination happens.

Second, you might remember that your left hemisphere maps to the right side of your body and your right hemisphere maps to the left side of your body. What you see with your right eye is processed with your left hemisphere and what you see with your left eye is processed with your right hemisphere.

And finally, generally speaking, the ability to produce language is a task performed by the left hemisphere.

If you found any of those facts confusing, take a minute and read them again. They are going to be necessary to understand the findings in Gazzaniga’s study.

With that background, let’s return to the study. This is going to get a little complex, but take it slowly. I promise the payoff is going to be worth it.

The Experiment Setup

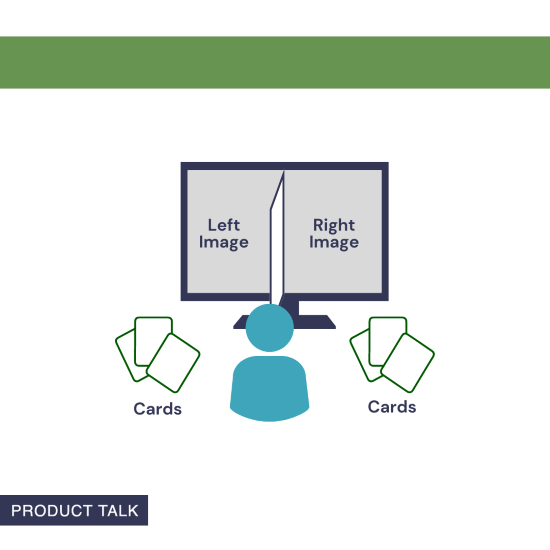

Imagine this: You are sitting in front of a computer screen. There’s a divider at your nose, so you can only see the right side with your right eye and the left side with your left eye. On the table, there are two sets of images on cards, one near your right hand (visible to your right eye) and one near your left hand (visible to your left eye).

This is what the participants experienced. Gazzaniga flashed an image on the right side of the screen and asked participants to choose a related image from the set of cards near their right hand. He did the same with the left side of the screen and asked participants to select a related image from the set of cards on the left side of the screen.

Here’s one set of images that Gazzaniga used:

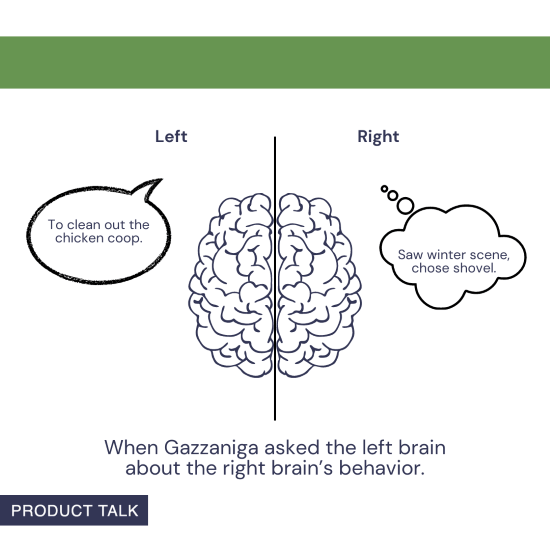

- Left eye processed by the right hemisphere: winter scene

- Right eye processed by the left hemisphere: chicken foot

When he asked the participant to pick out a related image with each hand, he did what you might expect. Here’s what he chose:

- Left hand processed by the right hemisphere: shovel

- Right hand processed by the left hemisphere: chicken

If you imagine the setup in your head, it’s pretty straightforward. Here’s where it gets clever.

Gazzaniga then asked the participant why he chose the shovel.

Now remember, participants were split-brain patients, so the right hemisphere can’t talk to the left hemisphere. And items shown to the left eye are processed by the right hemisphere. And finally, the left hemisphere is responsible for language production.

The right hemisphere saw the winter scene and the right hemisphere selected the shovel. But Gazzaniga is effectively asking the left hemisphere why it did so.

If you aren’t already familiar with this study, you might guess that the participant didn’t know why he picked the shovel. After all, the left hemisphere doesn’t know.

But that’s not what happened. And that’s why this study is so great.

The Surprising Finding

The participant explained that he picked the shovel because you need a shovel to clean out a chicken coop.

Wow! What’s happening here?

The left hemisphere is being asked to provide a rationalization for a behavior done by the right hemisphere. There’s no way the left hemisphere can know the answer.

But that didn’t keep the left hemisphere from generating an answer. It simply used the data it did have, the chicken and the chicken foot images, to create a reason for his behavior. Even though that reason had no basis in reality.

Now if this study was limited to split-brain patients, it would be interesting, but not that relevant to us. So why did I take the time to explain this complex experiment?

It turns out split-brain patients aren’t the only ones who fabricate reasons. We all do it. – Tweet This

Gazzaniga named this tendency to rationalize our behavior even when we can’t possibly know the reason as the “left brain interpreter” and later studies have shown that we all have an active “left brain interpreter.”

We need to reconcile the present with the past and when information is missing, our brains simply fill in any details that make the story coherent.

This is exactly why in Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman claimed, “A remarkable aspect of your mental life is that you are rarely stumped.” Your brain will gladly give you an answer.

It’s also why Kahneman argues confidence isn’t a good indicator of truth or reality. He argues, “Confidence is a feeling, which reflects the coherence of the information and the cognitive ease of processing it.” Not necessarily the truth.

As long as your brain can summon a compelling story, it will feel like the truth—even if it isn’t. – Tweet This

What This Means for Product Managers

As a Product Talk reader, you already know that interviewing can be an effective way to develop a deeper understanding of your customer’s world.

But now that you know about Gazzaniga’s study, you should be wondering how this impacts what you learn in interviews.

And the answer is simple. It has a big impact.

You can’t simply ask your customers about their behavior and expect to get an accurate answer. Most will obligingly give you what sounds like a reasonable answer.

But you won’t know if they are telling you about their ideal behavior or their actual behavior. Nor will you know if they are simply telling you a coherent story that sounds true, but isn’t true in practice.

If you build a product based on your customer’s ideal self, you might get the initial sale, but you’ll struggle to engage them, and you’ll churn through customer after customer.

You’ve probably experienced this as a customer yourself. You pay for that gym membership only to realize you don’t use it. Or you load up on vegetables at the grocery store, only to toss them out a week later when they go bad.

You’ll suffer an even worse fate if you build a product based on a coherent story that simply isn’t true in reality.

I learned this the hard way. Back in 2007, I worked on a product that helped big company recruiters recruit candidates.

At that time, the hype in the recruiting industry was around recruiting passive candidates—candidates who were currently employed, but open to new opportunities. There was a belief (and probably still is) that passive candidates were better candidates than active candidates—those who were unemployed and ready to apply to jobs right now.

If you read any of the thought leaders in the recruiting space, they were all talking about recruiting passive candidates. And if you interviewed big company recruiters, which I did, they would tell you that getting access to passive candidates was the dream.

So we built a passive candidate recruiting solution.

There was only one problem. Big company recruiters are incentivized to fill seats fast and the fastest way to fill seats is with active candidates. Passive recruiting is a long-game. Our product flopped.

It was the equivalent of selling hard-to-cook vegetables across the street from a McDonald’s. Our customers wanted to eat healthy, but it was so much easier to just buy a Big Mac.

It wasn’t due to a lack of research. It was because we asked the wrong questions. We built a product based on a coherent story told by both the thought leaders in our space and by our customers themselves. But it wasn’t a story that was true in reality.

If you want to build a successful product, you need to understand your customer’s actual behavior—their reality—not the story they tell themselves. – Tweet This

How to Ask Better Customer Interview Questions

Too often, we ask direct questions. We ask, “What matters to you when buying a pair of jeans?”

Or we ask, “How often do you go to the gym?”

But these types of questions invoke our ideal selves and they encourage our brain to generate coherent but not necessarily true responses.

You rarely want to ask your customers about their behavior. Instead, you want to get them telling specific stories. – Tweet This

Instead of asking, “What matters to you when buying a pair of jeans?”, start with, “Tell me about the last time you bought a pair of jeans.”

Instead of asking, “How often do you go to the gym?”, ask, “How many times did you go to the gym last week?”

You can follow up both with a question like, “Is that typical?” This can help surface if the last time was unusual. If it was, ask about other instances.

But don’t let your customer generalize. If they start off with, “Usually I …”, encourage them to tell you another story of a specific instance. You’ll get more reliable information.

This indirect approach is counterintuitive. You want to learn what factors they consider when buying a pair of jeans or how often someone goes to the gym. But you can’t trust the answers to these direct questions.

Instead, you need to ask about specific instances of actual behavior to indirectly get at what you are trying to learn.

This one change will dramatically improve the quality of what you learn in your customer interviews.

Try It For Yourself

Still skeptical? Let’s try a little exercise.

You might remember that I’m conducting product manager interviews. See here, here, and here.

Imagine that I’m interviewing you and I ask you, “How does an idea go from concept to launch at your company?”

This is an easy enough question. Take a minute and write down a sequence. Don’t just think about it in your head. Commit it to paper.

Okay, now think about the last product change that you released. Pick something specific.

Now take a minute and and jot down the process it went through to go from concept to launch. Again, don’t do this in your head. Write it down.

Now compare your two sequences. I’m willing to bet they aren’t the same.

If you are like every single product manager I have ever interviewed, your first list represents your ideal self, whereas your second list represents reality.

Your first list probably includes things like interview customers, run usability tests, look at metrics, get feedback from stakeholders, a/b test it, release it only if it beats out the control.

Whereas your specific project list probably only includes a subset of those things.

And that’s okay. Reality rarely lives up to the ideal. You can’t possibly do all of the things you know you should do on any given project.

But as an interviewer, if I’m trying to understand what product management looks like today, I want to uncover what you are actually doing, not what you hope to do.

And the same is true for you and your interviews.

Did you find this article helpful? I’ll be continuing to write more about how to get the most of your customer interviews in future weeks. Subscribe to the Product Talk mailing list to follow along.

Hi Teresa,

Did that customer who spoke about the jeans return the jeans for a lack of fit? Perhaps she trusts that brands fit and that is why she bought them online? My point is that while people may buy clothes online, they will go ahead and return them if they don’t fit well. So the original criteria of fit may actually hold in the end.

Hi,

Thanks for the comment. The point is not that fit isn’t a criteria. It’s that other criteria—the ease of buying online or the feeling of getting a good deal—trumped fit.

Imagine if you were a product manager responsible for designing a new line of jeans. In this scenario, it wouldn’t be enough to design the best fitting jeans. As your customer isn’t going to a store to try them on. The ease of online shopping and the lure of brand loyalty and a good deal trump fit. So you’d have to figure out a strategy to compete on those terms as well as fit.

Teresa hi, I wanted to complement you on this article. Sage advice.

I very often find myself advising -> “the most common mistake in customer research is asking the wrong question”. Well done on a great article that very clearly outlines how our intentions and actions are hidden from ourselves.

Thanks Jane

Jane, thanks for the comment! I spend a lot of time helping teams revise question guides and this is easily the biggest mistake I see.

Hi Teresa, Excellent article. I had the same realisation after reading Daniel Kahneman. We discovered that requirements gathered during process driven projects were much more accurate than others. If a project was to, say, automate an existing process the natural first step was to capture the existing process. However when it was something else such as ‘we need an app for managing expenses’ we did requirements gathering interviews and workshops.

In the second we asked what the users wanted. In the process driven projects we asked what they do today. So in the non-process projects we saw this behaviour you have so eloquently described in this article.

in the process projects people told us what they do today and we asked questions such as ‘why do you do it that way’ and they would describe workarounds to problems they dealt with everyday. This gave us incredibly valuable data on which we based the requirements.

There is a caveat, simply drawing a process flow diagram wasn’t enough. We used a lean approach where we made the participants answer why they did every single step, what outcome they expected. This is what generates the most interesting information.

We actually set out to develop a tool to support this approach for product requirements. We did, it’s found at https://www.getskore.com although we’ve since shifted our focus to strategic process improvement and business transformation. The tool still does the job well we just don’t market it that way.

When describing this approach to others I tend to call it Jobs To Be Done, it sounds better than process!

Thanks again for a great article!

Hi Craig,

Thanks for sharing your experience. I love having people draw out their flow diagram and having them explain each step. It’s a great way to get rich context.

Teresa

Teresa,

I recently discovered your website and what a wonderful resource! Conducting effective customer interviews is a real challenge and I appreciate the information you’ve shared. Definitely a site I’ll share with others in my organization.

Thanks, Joseph! I’m glad you found it and are enjoying it.

Hey Teresa,

First time I’m reading your article – awesome read! I loved the experiment as well.

Thanks! I’m glad you liked it.

Hi Teresa,

I am an aspiring Product Manager looking to set foot into the field from Engineering. First off, I came across your blog yesterday and I must say that it has very valuable information…..so Thank you! I have been lucky to be a part of various “product related” activities at my current team of which “beta customer interview calls/ usage demo” was one. I noticed that a lot of times “asking the right questions” (not leading,with bias) is hard. This has given me fresh new insight….the bit about “split brain” is very fascinating.

Keep up the good work!

Best,

Ashwin