Have you heard? My new book Continuous Discovery Habits is now available. Get the product trio's guide to a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery.

Have you heard? My new book Continuous Discovery Habits is now available. Get the product trio's guide to a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery.

Back in March, I spoke at ProductCamp Cascadia (an online conference hosted by ProductCamp Portland, ProductCamp Seattle, and ProductCamp Vancouver) exploring the topic of design justice. I refined the talk and gave it again yesterday at IndustryConf.

You can either watch the recording above or read an edited transcript below.

Hi, everybody. Welcome to JEDI Training for Continuous Discovery Teams. I’m Teresa Torres. I work as a product discovery coach. I’ve had the luxury of working with teams all over the world, and I teach them a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery. The reason why I like to share that is in today’s talk, we’re going to get into my continuous discovery framework.

And I like to set the tone that this framework was developed and co-created with dozens of teams from all over the world. Some in really small companies—as small as two founders—all the way up to global conglomerates with hundreds of thousands of employees.

I’ve worked with teams in all industries—regulated industries, consumer companies, B2B companies. It’s a framework that’s been well tested and works in a lot of different contexts.

Is this what you pictured when you heard the word JEDI? Let’s reset your concept of this word.

So today, I’m going to talk about JEDI training. Many of you may have had this in mind when you saw the title, but I’m actually hoping to reset your expectation a little bit, because today we’re going to be talking about justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Here’s how I’m redefining JEDI training in a product context.

I want to be really clear that I personally am not an expert in this topic. In fact, the events in the world in 2020 are what really motivated me to dig in and start to explore this topic. I really am just a beginner, but as I’ve started to explore it, I’ve realized that a lot of the design principles that are coming out of the design justice world—which we’ll talk about in a little bit—really layer nicely onto a lot of the principles driving continuous discovery.

Design principles coming out of the design justice world complement the principles driving continuous discovery. – Tweet This

So what I’d like to do today is take my continuous discovery framework and talk about how we might adjust or modify it to help us build more just or more equitable products.

Why Design Justice Matters

I want to start by talking a little bit about why I think this is so necessary. In 2020, we saw a lot of social justice issues arise around the world. We know in the tech industry that we’ve had challenges for a long time in terms of the diversity of our employees. But we also see these challenges show up in the types of products that we build.

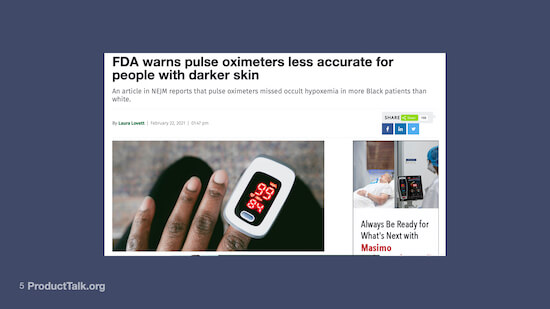

Pulse oximeters are a critical medical device during the COVID-19 pandemic. But they don’t work equally for everyone.

I want to start with a couple of examples. The first is a pulse oximeter. You may not be aware of this. This is a little device that’s become much more commonly known this past year with the COVID-19 pandemic. It measures the oxygen saturation level in your blood.

And it turns out this device works better if you have fair-colored skin than if you have darker-colored skin. So what we’re seeing is this product—which is actually a pretty critical health device for measuring how severe, for example, your COVID-19 case is—works better for some people and not as well for other people.

We’re seeing an example where some of the biases that show up in our communities are also showing up in our products. Now, most of us don’t work on medical devices, but we do see this show up in our more everyday products.

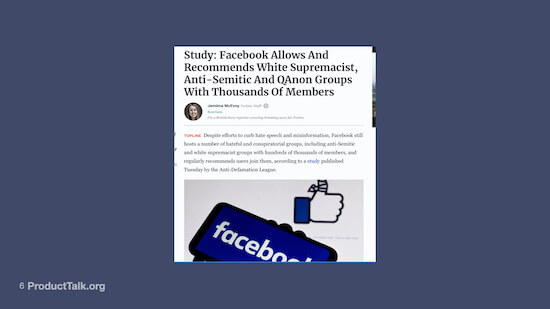

Facebook has come under fire for a wide range of problematic outcomes, including the proliferation of hate groups.

We saw in 2020 Facebook get hammered for their role in spreading misinformation and for their role in supporting hate groups. Maybe not actively, directly supporting hate groups, but allowing them to flourish on their platform.

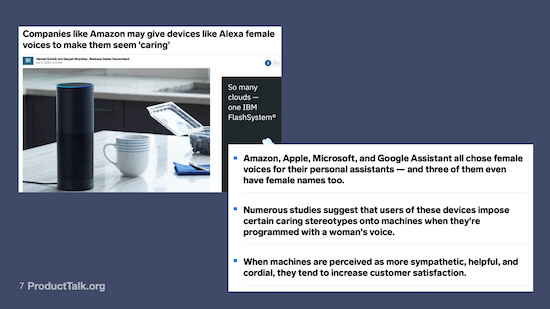

Many tech companies that make voice assistants justify their use of female names and voices by saying that’s what people prefer. But this isn’t the full story.

Another one that I see come up a lot is this idea of why all of our voice assistants—we’re talking about Siri, Alexa, Cortana—why they all have female names. And these companies have taken criticism for this before. The way that they defend their choices is they say, “Look, we did discovery. We did the research. We talked to our users and they prefer female names.”

What’s happening here is that we’re seeing a bias in our communities where we associate female names with a caring trait and therefore we’re replicating or perpetuating that bias in our products. But there’s a little bit more to the story here.

When we think of a “caring woman,” most of us imagine someone like the woman shown here.

For most of us, when we think about a caring female, we tend to picture someone like a nurse, maybe a school teacher, maybe a caregiver. Right?

When we think of a “caring woman,” most of us picture the woman on the left rather than the woman on the right.

We don’t think, for example, of a scantily clad woman in a video game. Why am I showing you this? The woman on the right is Cortana, she’s a character from the video game Halo. You might also know that Cortana is the name of Microsoft’s voice assistant. So when we’re looking at how biases show up in our products, I don’t think it’s as simple as they did the research and people think that women are more caring and they want their voice assistant’s name to be a female name. Obviously there’s a little bit more going on here.

Choosing female voices isn’t simply a reflection of users’ preferences. There’s bias at play here.

Even if it was that simple—we prefer female names because they’re caring or female voices because they’re caring—this comes out in our research because of the existing biases and existing hierarchies in our communities.

When we don’t stop to examine our biases, we end up building them into our products.

What’s happening is we’re building those biases, those hierarchies, those social inequities into the products that we’re building.

We’re building our existing biases, hierarchies, and social inequities into the products that we’re building. – Tweet This

We need to start asking ourselves how we can create products that contribute to a just, equitable, diverse, and inclusive world.

For me, this raises the question of how do we avoid this? How do we create products that contribute to a more just, more equitable, more diverse, and more inclusive world?

And so that’s what I want to talk about today. And again, I want to reiterate I’m really at the beginning of my journey.

My goal today is just to share some of the early thoughts that I’m having to give you some questions to ask. I’m not going to have a lot of answers for you. This is a big, hard topic, but I’m hoping it starts the conversation. And we all get a little better about asking these questions and looking at how we can contribute to a more just and equitable world.

Designing With, Not For

This quote illustrates the power we all have to influence the products and world around us.

I’m going to start with this quote by Steve Jobs, where he basically says that everything around us in the world was created by people. And those people were no smarter than us. And what’s great about that is it means that we can change it. We can influence what we see in the world. And realizing that gives you such a strong sense of agency. It really changes your life forever.

When we realize that we can influence the world around us, that gives us a strong sense of agency. – Tweet This

This quote is really inspiring. It means we get to create the world that we live in, but it also comes with a strong sense of responsibility. When we look around the world and we see these unjust products, these inequitable products, we have to start to ask, “How can we contribute to solving this problem?”

One of the principles of the design justice community is to design with, not for.

I recently read a book that really helped formulate some of my thoughts around this. It’s called Design Justice. And one of the principles from this book is to design with and not for. Design with your customers, design with your constituents, not for them.

I really love this because I think it gets at the heart of continuous discovery. Why are we continuously engaging with our customers? Because we want to make sure that we’re designing with them and not for them.

Why are we continuously engaging with our customers? Because we want to make sure that we’re designing with them and not for them. – Tweet This

I really want to emphasize that this is not how most of the tech industry works today. In fact, you might’ve heard a quote by Henry Ford. He said, “If I had asked customers what they wanted, they would’ve said faster horse.” Steve Jobs even said, “Customers don’t know what they want until we show it to them.”

We have some hubris in the tech industry where we believe that we’re the experts and that we can design for people. So here’s what I want to clarify. We are experts in technology, but our customers are experts in their own lives, their own needs, their own pain points, and their own desires.

What we want to do when we talk about “designing with” is we want to combine this expertise, our expertise with technology, their expertise with their own lives and their own needs, and really co-create solutions together. And this co-creation mindset is a little bit different from what a lot of us are used to.

When we have a validation mindset, we assume we are the experts. This can cause all kinds of problems.

In fact, a lot of teams operate on a validation mindset. So a validation mindset is when we say we’re the experts, we’re going to come up with the solution, we’ll design it, we’ll prototype it. And when we’re done, we’ll validate with our users. Did we get it right?

In a discovery world, we do need to do validation research. We need to confirm that what we built is going to work. But we can also work with our customers much earlier and try to move closer to this “designing with” mindset instead of a “designing for” mindset.

To get there, what I want to do is briefly talk through my continuous discovery framework, and then look at how we can layer on some of these design justice principles and see if we can get to more equitable products.

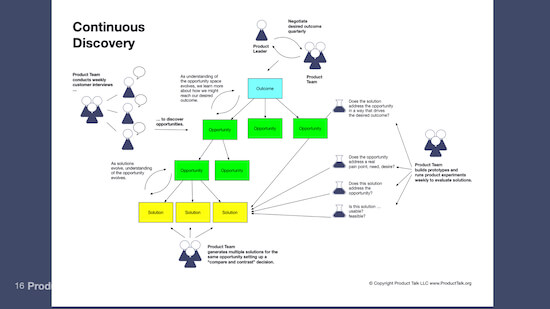

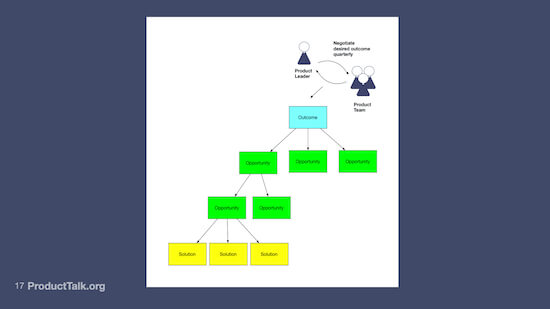

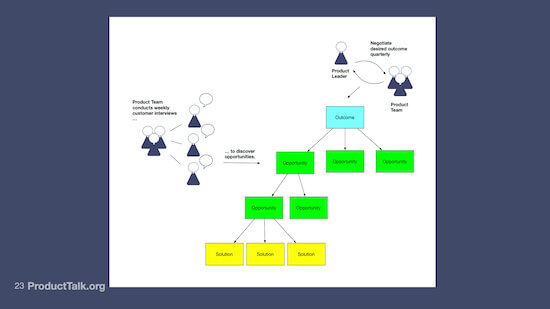

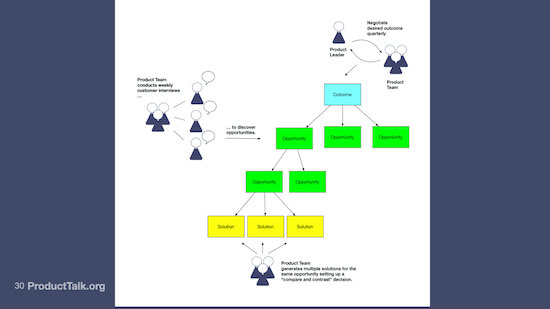

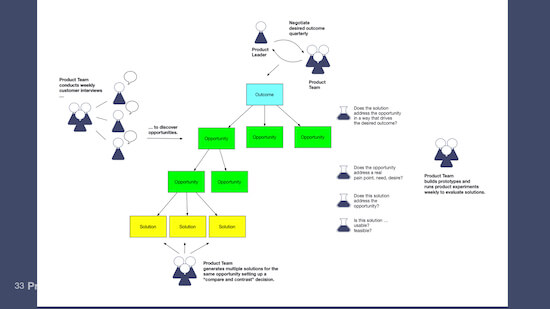

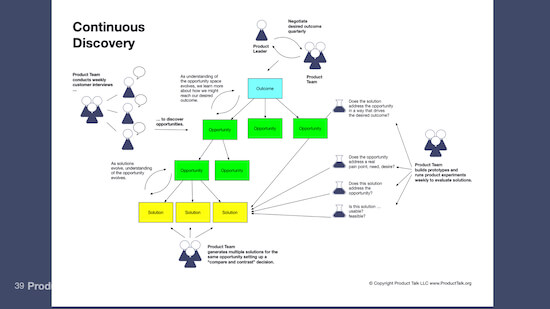

The opportunity solution tree is a visual guide to all the work that’s involved in continuous discovery.

This is my framework. If you’ve never seen it before, we’re going to briefly walk through it and then we’ll get a little bit more detailed as the talk goes on.

Setting an Equitable and Just Outcome

Continuous discovery starts with setting an outcome.

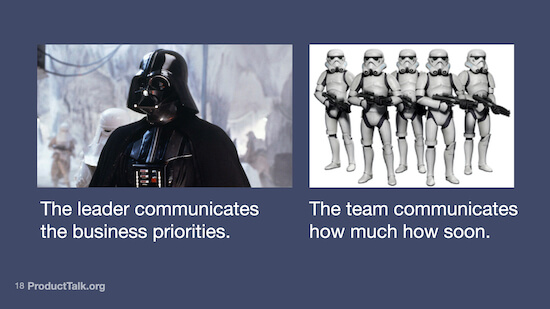

It starts at the top where we define a clear outcome. I teach an outcome-focused brand of product management. I believe that the negotiation of that outcome should be between the leader and the product trio.

What do I mean by the leader? The leader is your chief product officer, your vice president of product, your head of product. And your product trio is the product manager, the designer, and the technology lead who are working together to figure out what to build.

The product outcome is the result of a negotiation between the product leader and the product team.

The reason why this should be a two-way negotiation is because the leader is going to communicate what the business needs. So the leader is going to be able to communicate, “In this moment in time, here’s what we need from you.” And the team can communicate how far we can get.

I used to think product teams weren’t asking enough questions, but now I think we need to ask better questions.

Now during this negotiation, I think there are a few things that we can be doing to start to bring in some of these JEDI principles. The first is we need to start by asking better questions. In fact, this whole talk is going to be grounded in giving you a set of questions you can ask to start to evaluate the JEDI impact of your products. Are you building just and equitable products that support diversity and inclusion?

When we focus on growth, we tend to focus on the majority.

The first question that we can ask when we’re setting an outcome is, do we have to maximize that outcome? Or can we satisfice?

If you haven’t heard this word “satisfice,” it’s this idea of, is an option good enough?

And why is this important when we’re talking about outcomes? A lot of companies are hyper-focused on growth. That’s the business culture that we live in. And when we think about growth, if you work in a B2B context, I’m guessing that your company is really focused on landing large enterprise clients. That’s where the big money contracts are. It’s the biggest return on investment.

The challenge is if all of us in the B2B space focus on enterprise clients, who’s building software for the mom and pop businesses? And if nobody’s focusing on the mom and pop businesses, what impact does that have on our communities? Who’s being left out? This is a question where we can start to think about if we maximize for enterprises, are we going to live in a world where the only places we have to shop are Target and Walmart? That’s the reality.

We definitely need to bring in those big money enterprise clients, but can we also start to look at, can we service our underrepresented folks, whether that’s small mom and pop businesses, minority-owned businesses, or women-owned businesses?

To take a more just and equitable approach to creating products, we need to consider counterweights.

One of the ways to think about this—because you’re not going to change your business culture overnight—you’re not going to remove that focus on large enterprises—is you can start to think about counterweights. This means you set your primary outcome. That’s the outcome you’re trying to drive. You may not be able to change that it has to be “maximize large enterprise clients,” but can you counter it with a metric that helps you start to assess are we also serving the little guys, are we also serving the underrepresented business owners?

We can use these two questions together to start to assess what impact we are having by hyper-focusing on maximizing outcome.

And for those of you in the consumer world, we see similar challenges. The consumer world tends to be obsessed with driving engagement. Even to the point that we often build addictive products. The types of questions that we can ask—we probably have to drive engagement. That’s what keeps people coming back. That’s what pays the bills. But can we look at how to take the edge off the addictive quality? Can we look at who are the people who are maybe getting addicted to our products? Are we doing harm to them?

If we take a product like Netflix—those of us that work from 9 to 5 or 9 to 6 and have plenty of discretionary time, if we binge-watch a show on Netflix, it’s not that costly to our lives.

For those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who maybe work two full-time jobs at a minimum wage, they have very little discretionary time. An addictive product is going to have a much bigger negative impact on their lives.

So again, I’m not saying, “Don’t go after the big enterprise clients.” I’m not saying, “Don’t drive engagement.” It’s how do we ask these questions about if we maximize this outcome who’s being left out? Is it possible to satisfice in some areas so that we can create value for the underrepresented folks? And can we set counter metrics or counterweights to make sure that we’re not just focusing on maximizing, but also trying to measure who else we might serve? Who are we leaving out? How do we affect that?

Is it possible to satisfice in some areas so that we can create more value for underrepresented folks? – Tweet This

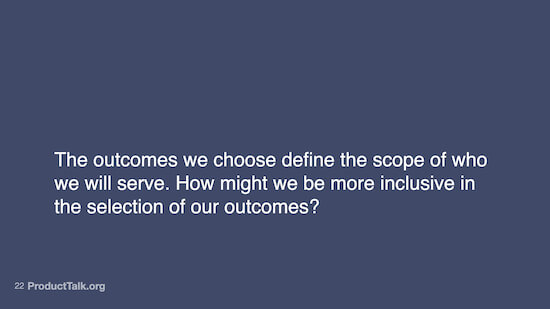

Our outcomes define the scope of who we will serve, so we need to be more intentional about creating inclusive outcomes.

Here’s the short of it: The outcome that we choose defines the scope of who we’re going to serve. So when you’re choosing your outcome, I want you to think about who you are including. And who you are leaving out. No product can serve everybody. Every product person knows this.

When we try to serve everybody, we build a product that barely works for anybody. So I’m not suggesting that your product has to serve everybody equally well. What I’m suggesting is that you be intentional about who you’re deciding to serve and who you’re deciding to leave out so we don’t end up with these unintended consequences where we have products like pulse oximeters that don’t work as well for people with darker skin. That wasn’t an intended consequence. That was because we weren’t intentional about who we were trying to serve.

Create More Inclusive Weekly Touchpoints with Customers

Conducting regular interviews with customers is a keystone habit for continuous discovery.

The next part of my continuous discovery framework encourages teams to interview their customers weekly. And the goal of those interviews is to discover opportunities.

An opportunity is a customer need, a customer pain point, or a customer desire. This is where we’re deciding which problems to solve. This is where that “designing with” instead of “designing for” principle really comes into play. It’s really easy to work with our customers to identify the right types of challenges to go after.

Working on a product team involves making product decisions every day.

The reason why I encourage a continuous cadence is that we’re making product decisions every day. Some of them are big. What goes on our roadmap? What strategy do we go after? Some of them are small. Where do we expose this feature in the interface? What do we label this button? But all of them benefit from some customer input.

We want to infuse customers’ unmet needs, pain points, and desires into our work. This is why I encourage teams to engage with customers every week.

As a result, I like to see teams engaging with customers every week. When we do this, we test our ideas before they’re ready. We share pencil sketches, we share half-baked ideas.

Talking to customers every week enables us to co-create with them.

And when we’re willing to do that, we start to shift away from that validation mindset that I talked about earlier toward this co-creation mindset. We’re co-creating with our customers and we’re starting to design with, instead of for.

I can’t emphasize this enough when I talk about co-creation. I’m not saying, “Ask your customers what you should build.” I’m saying, “Combine your knowledge of what’s possible with technology with their knowledge of their life and their needs and their context, and use that combined effort to start to think about how technology can impact people’s lives.”

Combine your knowledge of what’s possible with your customers’ knowledge of their life, needs, and context, and use that combined effort to start to think about how technology can impact people’s lives. – Tweet This

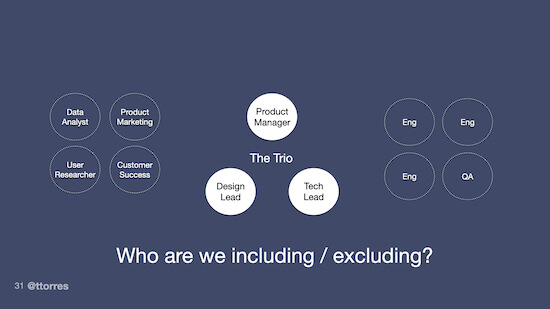

As we conduct more customer interviews, we need to start asking ourselves, “Who are we including and excluding?”

As we’re interviewing, we want to think about how JEDI concepts come into play. If we’re using our interviews to discover opportunities—the needs, pain points, and desires that we want to address—we want to start by asking, “Who are we including in our interviews and who are we leaving out?”

In the tech industry, we tend to be male dominated, white dominated, middle to upper socioeconomic class dominant, cis-gender dominant. We see the dominant races, ethnicities, genders, able-bodied people, etc.

This is who dominates the tech industry. And we tend to interview people like us. Because we’re recruiting from our networks. Our initial pool of users come from our friends and family. Even if we’re recruiting from within our products, we tend to be serving people like us.

This is why in cities like San Francisco, we get 17 startups that will deliver food, but we don’t get companies that are serving underrepresented folks, because those people aren’t involved in choosing the opportunities that we’re going after.

One of the easiest things you can do is start to ask this question, “Who are we including?” Now, it’s not going to be easy to change who you’re talking to, because you need to be able to find people who are not like you. And this is where I don’t have all the answers for you, but I want to encourage you to just start asking these questions. How might you reach out to more diverse folks?

And think on multiple dimensions. Not just race and ethnicity or gender, but also abilities. I know with a lot of websites, they end up having really small print because they don’t test with anybody over 45. There are a lot of dimensions to this.

What I want to encourage you to do is to take a continuous improvement mindset. You’re not going to wake up tomorrow morning and suddenly be able to interview a diverse set of people. So how can you make next week look a little better than last week? How can you get a little more diverse over time so that you start contributing to creating more just, more equitable products?

Extracting value without adequate compensation is a big topic within the design justice world.

The second question we can ask when interviewing is, “Are we extracting value without compensating?” This is a big topic that comes from the Design Justice book. And it’s really looking at, are we giving somebody $25 and extracting a huge insight that drives our multimillion-dollar product business? Is that really a fair trade-off?

Now, again, I don’t know the answers here. I don’t know what that looks like. I know in an enterprise context when getting insights from customers, we probably shouldn’t turn around and charge them for that product. But you do need to make money. You need to charge some of your customers, but can we find a better balance of compensating our participants for the value that they’re giving us?

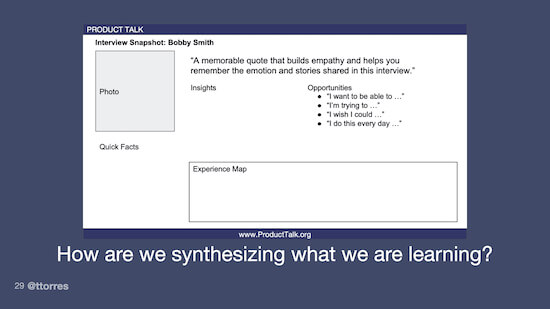

When you start regularly interviewing customers, it’s important to consider how you are synthesizing what you’re learning.

The third question we can ask when interviewing is, “How are we synthesizing what we’re learning?” A lot of teams use user personas. The challenge with user personas is that we tend to generalize across a set of interviews. When we generalize across a set of interviews, we end up falling back to our stereotypes. Our personas tend to represent either the majorities or one-dimensional stereotypes of a minority that we see in our communities.

When we generalize across a set of interviews, we end up falling back to our stereotypes. – Tweet This

What I encourage teams to do instead is to not create personas, but to create what’s called an interview snapshot. That’s what you’re seeing on the slide here. It’s just a one-page template that summarizes what you heard in each interview.

So rather than generalizing across your interviews, you’re capturing in a one-pager what you’re hearing from each interview. This helps to remind you that you are designing for a set of unique individuals rather than generalizing to this ideal customer that really is going to end up serving the majority and leaving out underrepresented folks.

I teach teams to choose a target opportunity and then focus their idea generation on just that opportunity.

Consider Underrepresented Folks During Ideation

The next area where we can start to look at how we’re serving underrepresented folks is when it comes time to ideate.

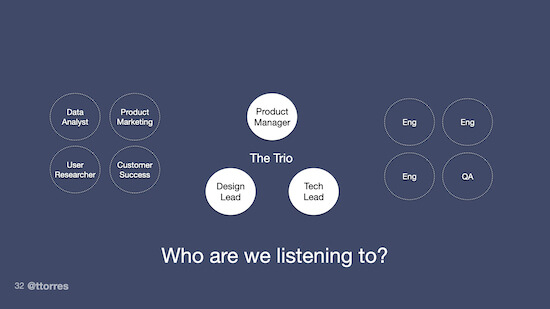

We can easily be more inclusive in our ideation teams.

Once we’ve chosen a target opportunity and we’re looking to solve it, what I typically recommend is that the trio start to invite other members of the team and get more diverse people involved in generating ideas. This way it’s more likely you’re going to end up with diverse solutions and solutions that work for more than just the dominant majorities in our industry.

You can start by asking, “Can we invite more diverse folks from our company into our ideation sessions?” You can even go further and say, “Can we invite some of our customers into our ideation sessions?” And you can go beyond that and ask, “How do we invite a diverse set of customers into our ideation sessions?”

Even when we include underrepresented populations in ideation, we need to take steps to ensure we’re actually listening to what they say.

It’s not enough to just invite people to these sessions. You also need to pay particular attention to group dynamics and who you’re listening to, which ideas get considered, which ones you choose to pursue. Because even when we get a diverse set of people in the room, we tend to fall back on our biases that we already see in our communities, where we tend to listen to the people in power, the people in the majority.

Even when we get a diverse set of people in the room, we tend to listen to the people in power, the people in the majority. – Tweet This

You want to be really thoughtful about who you are inviting and who you are listening to. If you have any women on your team, if you have any people of color on your team, if you have anybody who’s not able-bodied on your team, if you have anybody who doesn’t identify as cis-gender, ask them. They’ve probably had the experience where they were in one of your meetings. They suggested an idea, nobody listened to it, and then somebody in the majority suggested it. And suddenly people glommed onto it.

We don’t do this intentionally. I believe most product teams have good intent, but the impact is that we’re reinforcing the biases that we see in our community.

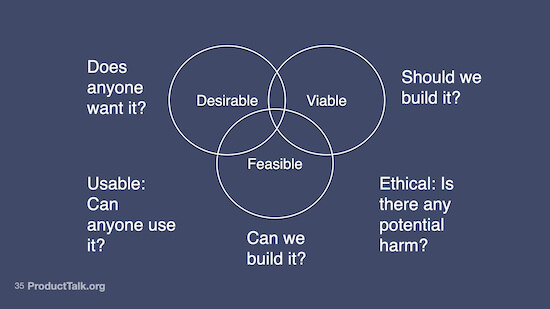

We have an opportunity to consider justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion when we examine our underlying assumptions.

Introduce JEDI Principles When Testing Assumptions

Finally, the last area that we can start to introduce some of these JEDI principles into our work is when we’re testing the assumptions that underlie our ideas.

There are several common categories our assumptions can fall into.

So what do I mean by that? Every single solution that we consider has a number of assumptions. We have desirability assumptions. Does anybody want it? Are they willing to do what we need them to do? Then we have viability assumptions. Should we build this? Is it good for our business? We also have feasibility assumptions. Can we build it? Is it technically possible? We also have usability assumptions. Can anybody use it? Can they find it? Do they understand it?

The category that we’re pretty bad at in the tech industry that I want you to start thinking about are ethical assumptions. Is there any potential harm?

There are several questions you can ask to get to more just outcomes. One of the most important is: “What data are we collecting?”

For a long time, I’ve thought about ethical assumptions as: What data are we collecting? Are we collecting data that our customers are comfortable with us having? Do they understand how we’re storing it? How are we using it? Are we selling it to third parties?

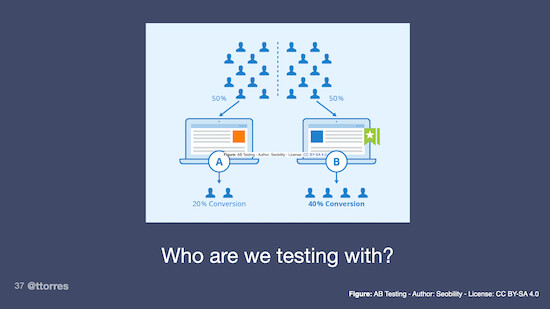

To be more just in our product outcomes, we must also consider who we are testing with.

But this is bigger than just the data that we collect. It also has to do with who we are testing with. So when we rely on A/B testing to tell us if an idea works or not, what we tend to look for is, across our whole population, does it work for more people in the variable group than in the control group?

The problem with this is that it could work better in the variable group for everybody in the majority and nobody in our underrepresented populations, and it could still pass our A/B test. So we need to learn how to get more sophisticated and go deeper with our testing and understand if it works for this population or if it doesn’t work for this population and stop thinking about everybody in our pool as the same.

As we’re designing solutions, we need to be intentional about asking who they work for and who they leave out.

Finally, as we’re testing our assumptions, we need to be really explicit about this and not just in our A/B tests, not just in the data we’re collecting. In our training sets, in our behavioral analytics, in our interviews, just across the board, taking a step back and saying, “Look, who are we designing for? Can we shift to a “designing with” mindset? Who is it working for? Who’s it leaving out?”

Further Your Understanding of Continuous Discovery

Remember: Every step in your continuous discovery journey is a chance for you to be more just and equitable.

Now, we went through this pretty quickly. This is a pretty broad framework. If it’s the first time you’re being introduced to it, I’ll briefly remind you. We talked about setting an outcome, interviewing to discover opportunities, mapping the opportunity space, choosing a target opportunity, generating solutions, and then testing those solutions quickly through assumption testing.

This is my continuous discovery framework. I think it sets the table nicely for thinking about how we integrate some of these JEDI principles.

If this framework is new to you, I have a book coming out this year. It’s called Continuous Discovery Habits. It’s coming out in late spring, early summer. Over the next 12 to 18 months, I will be working on a companion workbook for this book that starts to layer in some of these design justice principles.

Dig deeper into these concepts in the Continuous Discovery Habits book, set to be published in the late spring/early summer of 2021.

So if you want to learn more about this, if you want to dive in, I recommend checking that out. And then of course, like I said, I’m new to this world. And so I would love to keep the conversation going, answer your questions, hear your ideas. I would love to explore how we can work together to create more just and equitable products. Thank you very much.